You can leave a lasting mark on the scientific record. Adopt one of our mist nets, in your name or in someone else’s. There are only 50 mist nets up for adoption, so reserve your net now… or give this as a gift in the name of a fellow bird-lover!

By Trevor Lloyd-Evans

As banders, we are privileged to get up close and very personal with wild birds for a brief period in the Banding Lab at Manomet, before releasing them to go about their busy lives.

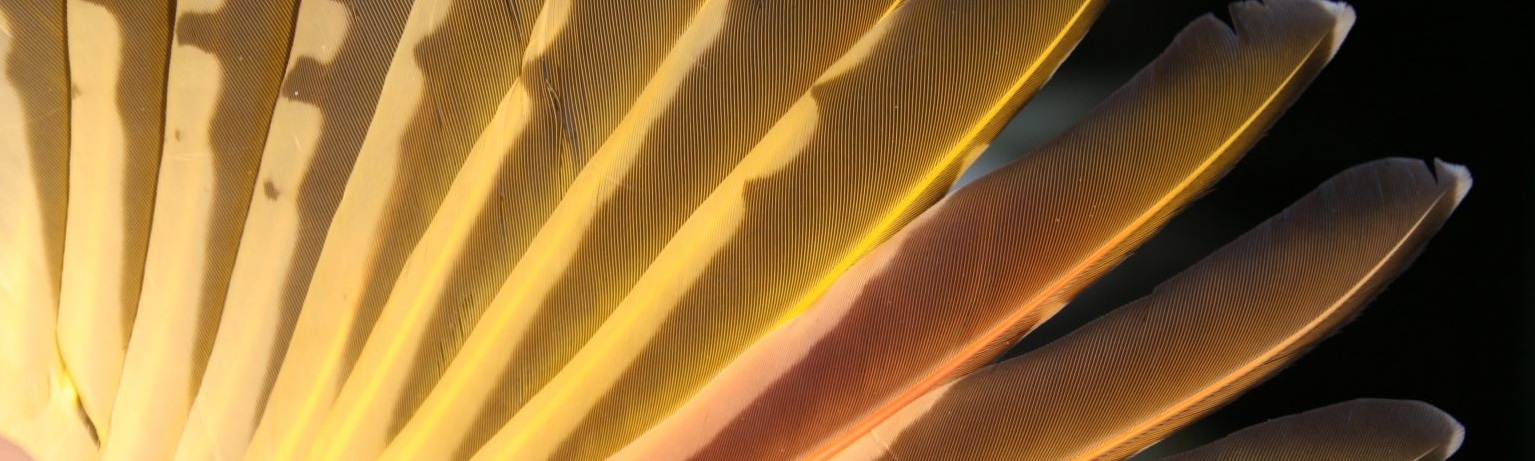

Besides the uniquely numbered US Fish & Wildlife band that contributes to our knowledge of local movements, migrations, longevity, and mortality factors, we rapidly note several observations in our database. Our banders routinely record data on wing chord (a standard measurement showing the proportions of a bird), mass, molt, visible subcutaneous fat, brood patches, parasites, and more details about the age and sex of the bird. This close-up examination provides much more than the best view available through our binoculars in the field.

Long-term banding data is critical to understanding the behaviors and lives of birds, as well as helping to prioritize conservation efforts. It helps us answer many questions about these species that we love, including “why does this bird suddenly have red feathers?”

As a result of many classification efforts on distribution, genetics, hybridization and museum specimen comparisons, banders have had to recognize either one, two, or three flicker species in North America since the 1950s. Currently, the Gilded Flicker of the southwest is its own species (Colaptes chrysoides), while the Yellow-shafted and Red-shafted Flickers are “groups” of the Northern Flicker (Colaptes auritus – also briefly named the Common Flicker).

Back to all

Back to all