Materials (content and photos) for this article were pulled from the Manomet archives.

August 4, 1969, dawned in Plymouth, Massachusetts; warm and overcast and seemingly average. But excitement was in the air! Thanks to a driven board of directors, one full-time employee, nearly 450 members from 27 states, and a core group of volunteers, the newly formed Manomet Bird Observatory opened its doors on that first Monday in August—just in time for the first migrants to arrive for fall banding.

“Manomet Bird Observatory has become a reality, the first of its kind on the Atlantic Coast of North America,” wrote Kathleen ‘Betty’ Anderson, Manomet’s first Executive Director, in the first-ever edition of the Manomet newsletter. “The value of the data acquired had already become evident. The response of the volunteer workers and of the public to the membership drive has enthusiastically ratified the decision to open permanently.”

Manomet’s history begins with Anderson, founders Rosalie and John Fiske, and a group of curious volunteer ornithologists relocating a small banding operation started by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to a property named Widewater owned by the Ernst family. This banding operation grew from 1966-1968 as bird enthusiasts came from near and far to take part, leading to discussions of creating a permanent research station. In 1969, Ruth Ernst donated the Widewater property for the establishment of a bird observatory.

From the moment the doors opened, MBO’s science staff and volunteers embraced solid scientific research and connecting people to the natural world. The data collected from Anderson’s banding operation had already contributed to two papers by the time MBO was born: A Migration Wave Observed by Moon-watching at Banding Stations by Ian C.T. Nisbit and W.H. Drury, and The Identification, Biology, and Medical Importance of Scutate Ticks (Ixodidae) in New England by Andrew J. Main, Jr.

In her history of Manomet Bird Observatory, Anderson wrote that “The first two years were a fast-paced blend of full-time banding, constant visitation (planned and unplanned), a busy education program, and growing recognition that a scientific staff would be needed if the observatory were to expand research beyond banding.”

Brian Harrington becoming Manomet’s first full-time biologist in 1972 and Trevor Lloyd-Evans joining the staff just a month later set in motion a solid foundation for Manomet’s long-term landbird and shorebird research. When Lloyd-Evans joined MBO in 1972, his primary responsibility was supervision of the banding program. His arrival at Manomet was also his first experience with North American birds, and the first weeks at MBO were an exciting introduction to a whole new suite of bird species in the hand.

As he acquired more knowledge of New England habitats, Lloyd-Evans initiated studies of breeding bird populations in the pine barrens of the nearby Myles Standish State Forest and surrounding areas, demonstrating that the greatest diversity of breeding birds in these fire-prone forests occurred approximately 10 to 15 years after a burn, rather than in the most mature pitch pine (Pinus rigida)-scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia) growth.

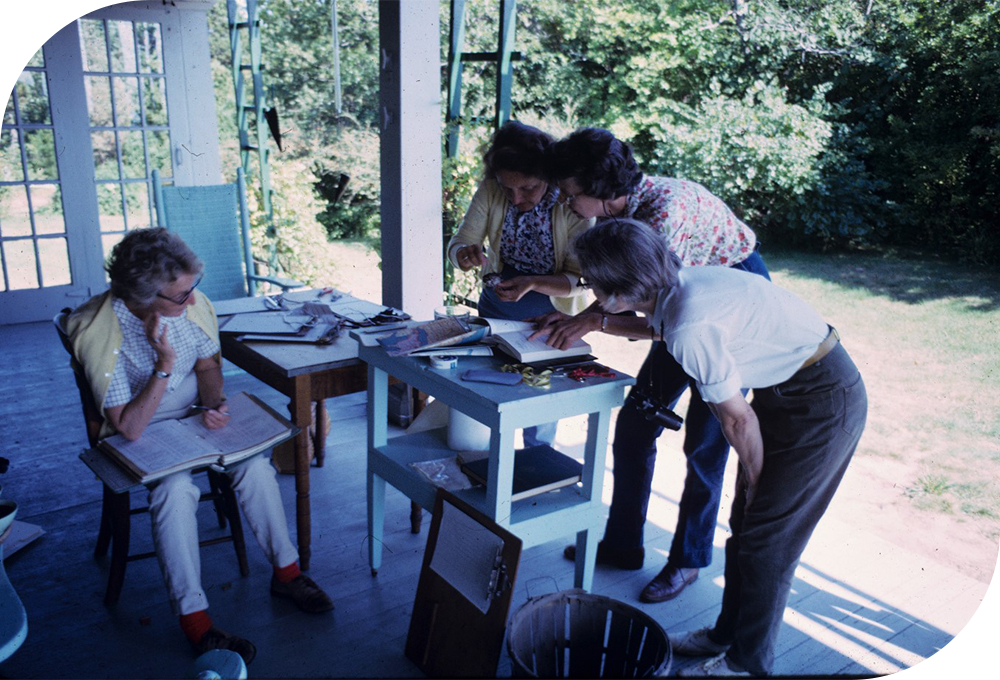

Education has been a pillar of Manomet’s work since the earliest days at MBO. Anderson and Lloyd-Evans spearheaded Manomet’s internship program which welcomed aspiring biologists and naturalists to partake in the organization’s already flourishing suite of research projects. Anderson describes the interns who came from all over North America, South America, and Europe: “we had people from all kinds of backgrounds, but, there, they were all on equal footing and it was a yeasty mix.” From seabird monitoring to landbird banding, the intern program has, to this day, trained thousands of young scientists. According to the 1984 MBO Annual Report, 90% of interns to that point had “continued to pursue careers in biology,” which still very much applies to our current generation of Manomet banding interns. Without these interns, there is no way that MBO could have accomplished as much as it did in those early years.

By 1973, Manomet had a core staff of scientists and seasonal interns running its varied avian research efforts. As research expanded, so did the need to fill gaps in data to inform better conservation practices. The goals of the founders were providing a site and opportunity for long-term studies of birds and other aspects of the natural history and ecology of southeastern Massachusetts. Activities at Manomet in these early years extended far beyond birds and Massachusetts. Research projects took staff from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego, from tropical forests of Central America to boreal forests of northern New England and Canada, from the ocean to the uplands, and from studies of pesticide pollution to measuring the absorption of radiation in wild birds.

A recognition of the need for better conservation practices inspired staff biologist Brian Harrington to begin the International Shorebird Survey (ISS) in 1974, a network of volunteer observers spread throughout the Western Hemisphere with the goal of documenting shorebird populations on a grand scale. The ISS, which was initiated with partners at the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), provided data that pinpointed areas of critical habitat for shorebirds.

Twelve years later, the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) was formed after development by the New Jersey Department of Fish, Game and Wildlife, World Wildlife Fund-US, and the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, partners at Manomet, CWS, and National Audubon. WHSRN, bolstered with the strength of some of the most prominent shorebird conservation groups of the time, dedicated its first site in 1986 on the Delaware Bay. Thirty-three years in, WHSRN now has 106 sites in the network with partners across the Western Hemisphere working to manage and protect land for shorebird conservation.

Meanwhile, Manomet’s Landbird Conservation program was gaining momentum on a hemispheric scale as well. Lloyd-Evans and Anderson had been leading expeditions in Belize throughout the 1980s to monitor wintering neotropical migrants. Belizean organization Programme for Belize came to Manomet after learning of their expertise for consultation in sustainable resource use within conservation areas. Similar to the workshops and trainings held by Manomet’s then-shorebird team, our landbird and forest scientists spent the next several years working with Programme for Belize to deliver instruction on sustainable practices to both benefit Belize’s local economies and protect critical land for wildlife.

In 1985, Manomet welcomed Kathy Parsons to the science staff. Parsons, a lover of wading birds (herons, egrets), initiated Manomet’s Estuarine Biomonitoring Program in 1986. The program, which ended in the late-2000s, was designed to inform conservation decisions for wetlands in the Northeast. Parsons worked with New York City Audubon to monitor heron colonies in New York harbor—the data collected from such monitoring later played an important role in a settlement with Exxon following the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989. Robert Tucker of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection said this in the 1994 25th Anniversary issue of Manomet’s former magazine, MBO Quarterly: “Because Kathy already had baseline data, her work was instrumental in achieving a settlement with Exxon.”

Taking Anderson’s place as Executive Director in 1984, Linda E. Leddy, who had been serving as Manomet’s Development Director, began taking a different look at how Manomet conducted its work. “Is it enough to know how an organism, habitat, or natural system works?” she asked. “How can we, as scientists, act to reverse the trends in species and habitat loss that we are documenting so efficiently?” Uncovering crucial information on bird migration, behavior, and populations had served a myriad of purposes toward improving land use, education, and more. Yet, studying just one area of earth’s natural systems would not be enough to effect change toward an overall more sustainable world.

Trevor Lloyd-Evans ca. 1980s.

Manomet’s current President John Hagan began his career at Manomet in 1986, when he joined the Landbird Program as a Senior Scientist. “From 1969 to the mid- to late-1980s, Manomet mostly worked on birds and ecological research,” he reflects. “In the 1980s, many North American bird populations were declining, and many of them were forest-dependent.”

Continental-scaled declines in migratory landbirds led Hagan and Manomet to organize and host a major symposium in Woods Hole in 1989. Nearly 400 scientists from throughout the Western Hemisphere attended and is well-remembered by participants today. This symposium was widely considered the “nursery” for what became Partners in Flight, a coordinated multi-agency, mutli-organization effort to reverse the declines in migratory landbirds—which is still active to this day. The Woods Hole symposium resulted in an award-winning publication by the Smithsonian Press and, along with the published proceedings, catapulted Manomet to national acclaim in landbird science and conservation.

The symposium sparked Hagan to ask “who owns” North American forests, and to work directly with them to improve management for these declining species. With the timber industry managing the majority of Maine’s forests, Hagan began building partnerships with the industry’s foresters to put this idea into practice.

After five years of working with the timber industry, Manomet had changed how tens of millions of forest acres were managed in New England. “It helped us recognize that our scope of influence was limited if we only worked with other bird biologists,” says Hagan. “By virtue of creating partnerships with people who were in a position of influence, we started to have a much bigger impact on the things we cared about.”

Around the same time, Manomet joined the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) in the Marine Observer Program in 1988. The program sent Manomet observers, contracted by NMFS, to accompany fishing vessels at sea to collect data on catch and bycatch (fish not targeted). These data would serve NMFS studies on population status of groundfish in the Gulf of Maine. There had been a marked decline in groundfish stocks in the 1980s in some of New England’s major fishing ports, causing major concern for fishermen and scientists. Manomet’s contract with NMFS created the beginnings of a possible solution to the decline of important fish species in New England. According to the fall 1991 issue of MBO Quarterly: “[Manomet] continues to provide NMFS with a fundamental building block for the development of workable management and conservation policies which should ultimately result in reversing population declines.”

By 1994, Manomet formed its Fisheries Observer Research Project in collaboration with NMFS, the Federation of Association of Atlantic Charterboats and Captains, the Bluewater Fisherman’s Association, and the East Coast Tuna Association. This project began Manomet’s long-standing work with the fishing industry in the Gulf of Maine; it not only deployed scientists to continue to conduct surveys for accurate data on fish populations, but also delivered interpretable analyses of these data to and worked with fishermen to grow their understanding of the relationships between their harvest practices and marine ecosystems.

“Manomet Bird Observatory was founded by a few people with a vision and the hope of providing a site and an opportunity for long-term studies of birdlife and other aspects of the natural history and ecology of this long-settled part of New England, always with the goal of aiding conservation,” said Anderson. Manomet’s work over its first 25 years expanded organically and opened the door to a broader understanding of the world around us. This understanding of how the many facets of our world are connected—and a belief that we cannot solve the complex challenges that we are facing by ourselves—has shaped our recent past and laid the groundwork for our future.

Read about our most recent 25 years and how we look to the future here, featured in the summer 2019 issue of Manomet Magazine.

Back to all

Back to all