This spring and summer, Manomet scientists and partners tagged over 30 Whimbrels with state-of-the-art GPS trackers in the southeastern U.S. and Arctic. Here’s where those birds are now.

In late May 2022, a team from Manomet and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service returned to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to continue our collaborative work studying Arctic nesting shorebirds. This year, we worked on several research projects including coastal plain shorebird surveys, a study of shorebird nest survival, remote audio monitoring of nesting birds, and a multi-year tracking study of nesting Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus). This is difficult work, and only possible thanks to consistent support from Manomet’s individual donors, as well as the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Mennen Foundation, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Manomet is deeply involved in Whimbrel research and conservation. In addition to this Arctic research, we are conducting a long-term study of juvenile Whimbrel migration and survival based in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. We also recently began monitoring Whimbrel on the Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana, a newly-discovered area of importance for these birds as they migrate to their Arctic breeding grounds from Central and South America. Located across the places these birds rely on most, our partners — the College of William and Mary in Virginia, Georgia DNR, and the University of Oklahoma — work with us to monitor Whimbrel populations during key times of year.

We are particularly interested in Whimbrels because they are a long-distance migratory shorebird facing steep population declines — about four percent per year — especially along the Atlantic Flyway. Whimbrels nest in the Arctic, which has the most rapidly changing climate in the world, and face threats along their extensive migration routes, including development, disturbance, land conversion practices, environmental damage from chemical and oil spills, and hunting.

Our research goals this season were to understand how Whimbrels use the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge during and after the nesting season, and discover important migration and wintering sites via GPS tracking. Combined, these efforts will help us better understand how Whimbrels use the landscape throughout their annual cycle.

Results in real time

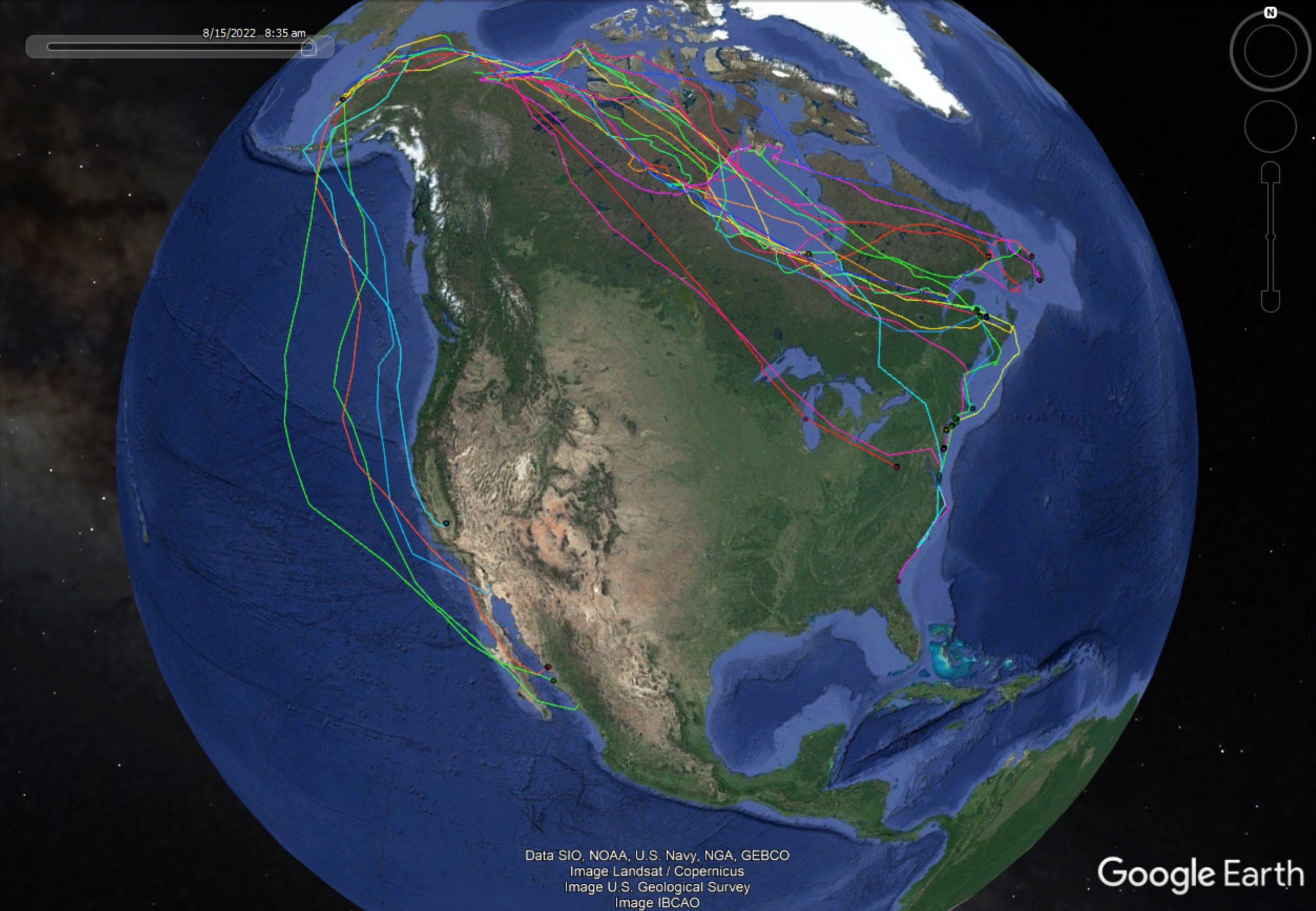

The work we are doing in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is exciting for many reasons, especially now that we can see the results of our work unfold before our eyes. Thanks to the data those GPS transmitters provide, we can see that Whimbrels on the refuge are currently migrating down the Atlantic, Central, and Pacific Flyways.

In 2021, we tagged two nesting pairs that each had one bird go east and the other go west to wintering areas on opposite sides of South America. All Whimbrels tagged elsewhere in Alaska have used the Pacific Flyway, wintering from California all the way to Chile. Our tracking data shows that the eastern and western Whimbrel populations converge in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. This means that the nesting population in the refuge is affected by challenges in locations as diverse as Arctic Alaska and coastal areas across the Canadian Maritimes, New York, Mexico, and Brazil, and many other places throughout the hemisphere.

This year in the Arctic was particularly challenging because of the late arrival of spring. Many shorebirds delayed nesting or went elsewhere as we experienced day after day of high winds, cold, and late snow. But Whimbrels are very site-faithful, and at least three of the birds we tagged last year returned to nest in the same valley, despite the harsh conditions. Leading up to our trip this year, I had been closely following the journey of “Sadlerochit,” a male Whimbrel that we tagged last summer who migrated to the coast of Virginia, and then on to Suriname for the winter. In late April, he flew to Louisiana to feast on crayfish before continuing up through the Great Plains to Arctic Canada.

On May 25, just before heading into camp, I decided to check the locations of our tagged birds. I saw that Sadlerochit was in flight crossing the Brooks Range at about 12,000 feet on the final leg of his migration back to his nesting site in the Katakturuk Valley of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge — the exact location of our field camp.

We caught sight of him on the same territory he used last year just a few days later. He attracted a mate, and they were one of the few pairs to hatch chicks this year. Of all the birds we tagged in 2022, Sadlerochit was the last to leave the breeding site as he was responsible for raising the chicks until they could fend for themselves. Both female and male Whimbrels share incubation duties, but after the chicks hatch, the males assume most of the responsibility of caring for the chicks, and the females typically leave several weeks before the males. As I write this piece in early August, Sadlerochit is in flight over central Canada, heading for the coast of Virginia, and then likely back to the same mangrove creeks in Suriname to spend another winter after a successful nesting season.

The rest of our tagged birds are scattered throughout the coasts of North America as they travel between migration stopover sites from eastern Canada to western Mexico. Over the next several months, we will follow their journeys to Central and South America and back north again in the spring. If circumstances and funding permit, we will return to the Arctic next spring to continue uncovering the secrets of these remarkable marathon migrants.

Back to all

Back to all