Alan Kneidel

Senior Conservation Biologist

Water, Water, Everywhere…

It was the third straight day of lashing rain, stuck in the middle of a coastal storm that would end up dropping 10 inches on outer Cape Cod. But this was no office day for the Whimbrel crew – Shiloh (Dr. Shiloh Schulte, Manomet’s Senior Shorebird Scientist) sat crouched behind a propped-up rowboat, an unsteady yet effective windbreak as he peered over occasionally to check the nearby noose carpet array. Liana (Liana DiNunzio, Shorebird Biologist) sat huddled among the dune vegetation, vigilantly monitoring the more distant traps.

Meanwhile, I strode ponderously through hip-deep water in the flooded marsh behind the sand ridge, the water rising rapidly as the king tide approached. Time was running out, the water soon to cover the traps, and then: Liana started sprinting! In a flash, she had a Whimbrel in hand, sheltering it in her jacket as she walked back to the truck – our mobile banding station. I started making my way to meet her, and after about 20 minutes in the warm, dry truck cab, the bird was successfully released, and the fieldwork complete for the season.

Closing the Information Gap

September 2024 marked the 10th anniversary of Manomet’s research on juvenile Whimbrel on Cape Cod. This work has focused on the deployment of satellite transmitters to collect data on juvenile migration ecology and survival, one of the key information gaps remaining in our understanding of this declining species. The results to this point represent the only tracking data of juveniles in the Western Hemisphere and have provided documentation of a non-breeding period in South America of up to 900 days before birds ever initiate northbound migration for the first time.

This September, our goal was to deploy four new transmitters, thanks to funding through the joint United State Geological Survey (USGS)-United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Science Support Program and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. This funding has allowed us to scale up our juvenile work to definitively answer our research questions. This work is just one component of Manomet’s Whimbrel conservation initiative that spans the Americas – from the tundra in the north, to the mangroves in the south – as we build a full life cycle demographic model and conservation plan for the species.

Whimbrel on the Wing

Fast forward two weeks to early October, and all of us have gone our separate ways, back in our routine of office work and daily meetings. That is, with a slight addition to our itineraries: feverish checks of the Argos satellite network website, where we can check on the progress of our tagged birds. Each tag transmits daily for about 10 hours, before then going dormant for the rest of the day, recharging its little solar panel. The data is relayed as frequently as every hour, so it is possible to get near real- time updates.

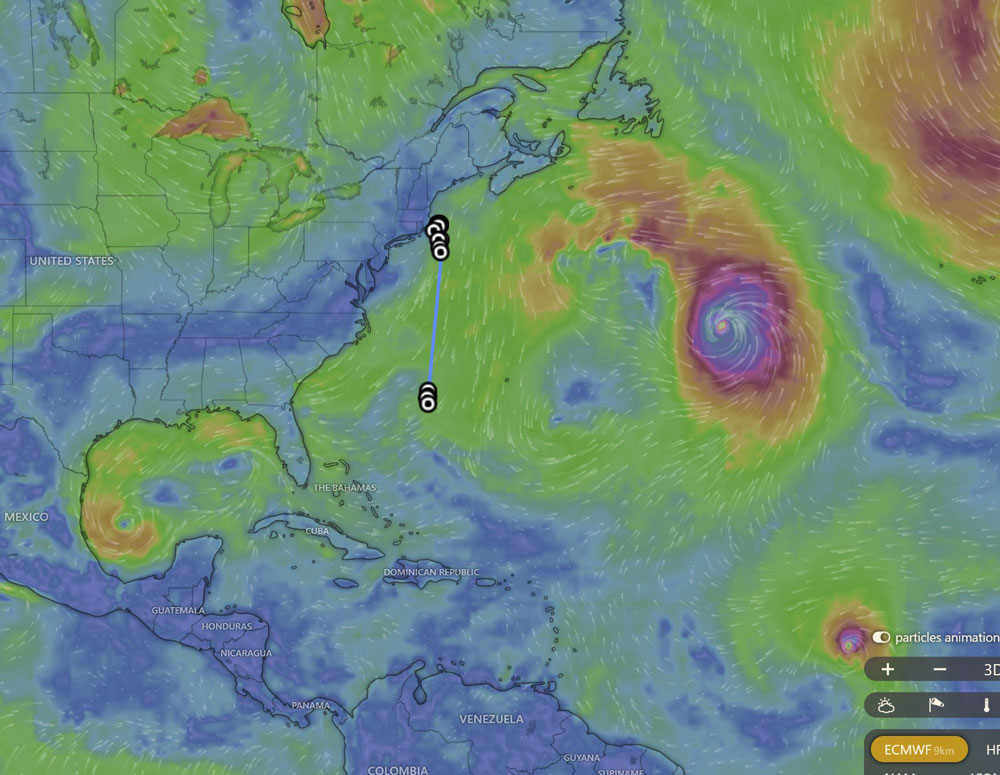

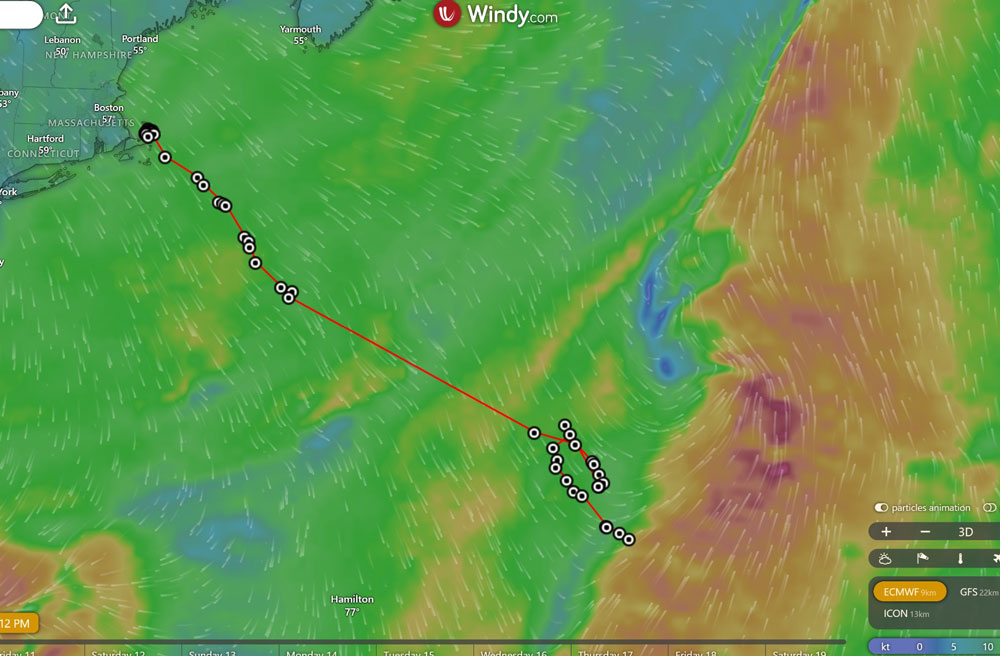

At last! Our birds were on the move, after completing their staging period on Cape Cod. What had us particularly on pins and needles, however, was the daunting gauntlet of tropical cyclones that were currently churning in the Atlantic. While migrating birds can carefully choose nights with cooperative tailwinds for departure, it can still be difficult to predict what will be happening thousands of miles, and multiple days, ahead of them. This was just the scenario presented to one of our tagged birds.

After starting on a reasonable trajectory for South America, the juvenile Whimbrel of interest got caught in a rotating storm for 18 hours, flying in circles and attempting to extricate itself from the cyclonic winds to get back on track. All the while, hundreds of miles to the south, Hurricane Milton was racing to the east to present the next challenge. Unfortunately, this bird’s tale was not destined to be a success story. The bird never escaped the storm and stopped transmitting: presumed dead.

And, what about the other three birds we tagged? It’s been a mixed bag of results, which truly paints a turbulent picture of the daunting prospects juveniles face on their first migrations. One died while still on the Cape after 2.5 weeks of daily commutes from Wellfleet marshes to Jeremy Point, likely falling victim to the talons of a bird of prey such as a Peregrine Falcon. The final two birds successfully arrived in Venezuela after threading their way through the Caribbean islands.

The first of these birds, however, quickly met its demise in a most mysterious fashion. After making landfall on the Islas Los Hermanos, a small archipelago of uninhabited islands just off the coast, the bird began giving an unusual signal, drifting northwest at one mile per hour over water. This signal continued for over a day, before going dark forever. We don’t know for sure what happened to this bird – it’s possible it got knocked out of the sky by a falcon or by a local human hunter, or perhaps it died along the shoreline and got washed out to sea.

The final bird of the banded quartet continues to report daily along the coast about halfway between Caracas and Maracaibo. The area this bird is using is well-known to one of our partners, Dr. Sandra Giner, a professor at the Central University of Venezuela. After sharing the location with her, she reports that the area has saltmarshes and intertidal mudflats and plays host to a large number of shorebirds that forage and roost there.

What’s Past Is Prologue

So, you might be wondering, what it’s like to put so much effort into deploying these transmitters, and then watch their individual stories play out like Shakespeareian dramas? I’d be lying if I didn’t say that sometimes I get carried away with following their migration stories, and maybe even a little obsessed. Especially when it comes to the juveniles, who we meet fresh from their flights out of the tundra, their bills still growing, their plumage spangled and golden. But a wise scientist works to find a balance between the greater research goals and the individual animals. At its core, this is a scientific study into the survival of juvenile Whimbrel, and the many threats they face. Built into that is an elemental story of life and death, and – as we’ve seen with the four juveniles our team tagged on Cape Cod this fall – no group of species threads that needle more dramatically than long-distance migratory shorebirds.

Back to all

Back to all