Dr. Juliana Bosi de Almeida aims to tackle shorebird conservation challenges across the Americas in her new role as Managing Director of Manomet’s Flyways program

Read this story in Portguese here / Leia esta história em português aqui

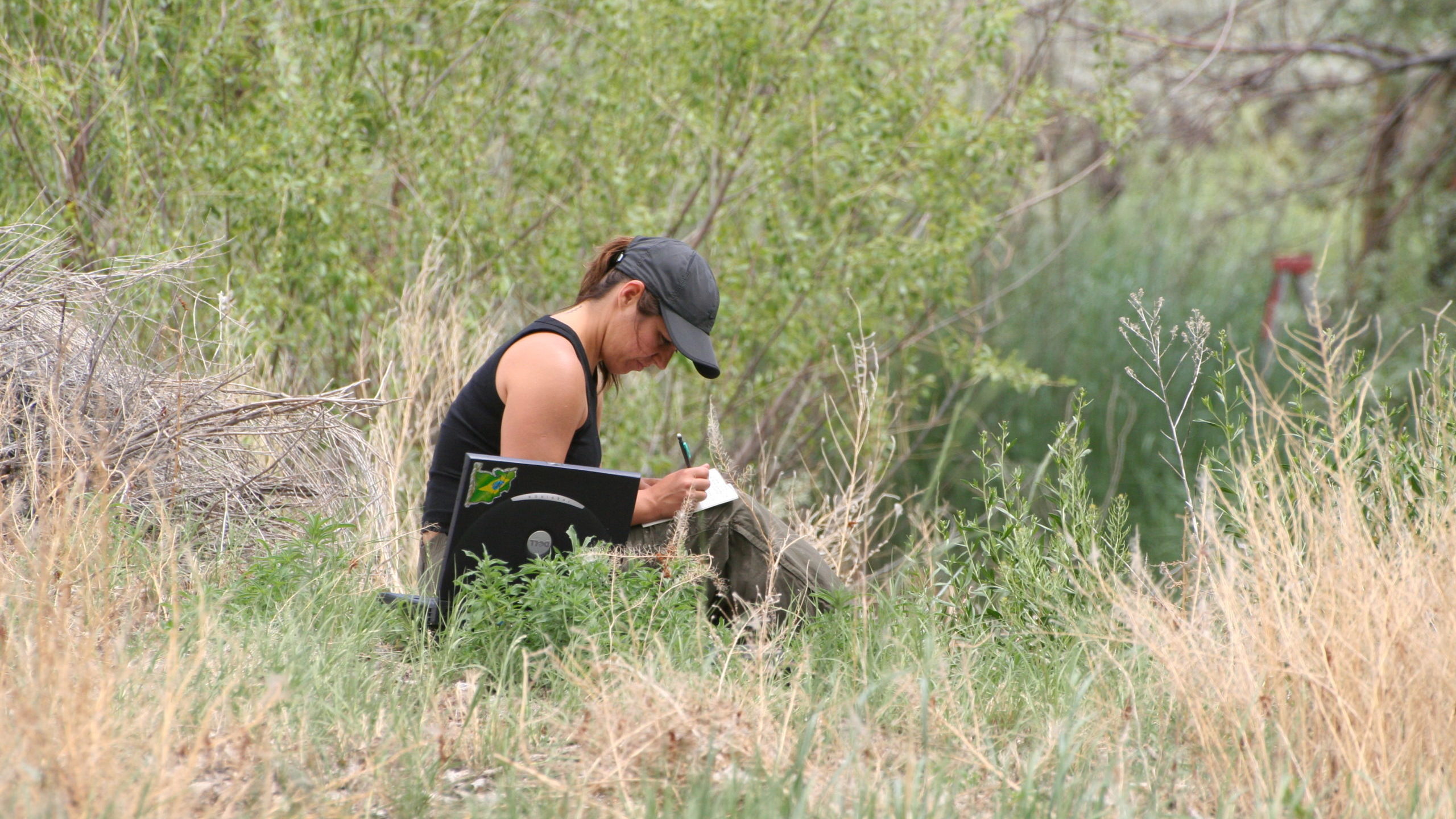

By Emily Renaud | Photos courtesy of Dr. Juliana Bosi de Almeida

Shorebirds are Dr. Juliana Bosi de Almeida’s life. She’s been studying the rapidly-declining bird group since the early 2000s when she earned her Ph.D. researching Buff-breasted Sandpiper population dynamics in South America through the University of Nevada.

“There’s something about their eyes… I don’t know how to explain it, but there’s something special and gentle in their expression that I’ve always been drawn to,” she says.

Born in Brasília, Brazil, Juliana grew up surrounded by the Cerrado biome, far away from shores and shorebirds. It was through her interest in behavioral ecology, specifically her master’s research on the Blue-black Grassquit’s mating system, that she discovered shorebirds and their fascinating behaviors. Over the last 20 years, she has contributed essential knowledge to shorebird conservation plans used throughout the Americas, most recently through her work at SAVE Brasil where she developed and led the organization’s shorebird conservation program.

In November 2022, Juliana joined Manomet as its new Managing Director of Flyways, working to streamline shorebird conservation efforts throughout birds’ annual lifecycles across the Western Hemisphere. We sat down with the Flyways team’s newest member to learn more about her love of shorebirds, the conservation challenges she’ll tackle in her new role, and why she hopes shorebirds someday become as beloved as sea turtles.

Q&A: Dr. Juliana Bosi de Almeida

Manomet: Where did your interest in shorebirds come from?

Juliana: Shorebirds’ lifecycles are fascinating. I love telling people who are new to shorebirds about how incredible they are and seeing their reactions, like how they travel from the Arctic to South America every year or how they can fly for five or six days straight without stopping.

I first learned about shorebirds from my Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Lewis W. Oring. Before I went to Nevada to study with him, I asked about the possibility of conducting my research project in Brazil. He then gave me a list of birds he wanted to work with, and one of them was the South American Painted-Snipe. The South American Painted-Snipe is a rare, understudied shorebird that occurs only in southern South America from a family (Rostratulidae) with only two species, each with very different mating systems. Since I’ve always been interested in bird mating behavior — and the fact that I love a challenge — I decided to learn more about this species for my Ph.D.

Once I made it to the United States, I got involved in more work focused on shorebird ecology with my advisor and his students, including research on Killdeer, Long-billed Curlew, and Buff-breasted Sandpiper. In the end, my heart was captured by the bird that shorebird biologists affectionately call a ‘buffy’ and I changed the direction of my Ph.D. I get emotional when I think about the time I spent working with my advisor; his passion for these birds is really what got me hooked on shorebirds and kicked off my career.

Why does shorebird conservation matter?

We need conservation to even have shorebirds. Early on in my career, I thought I was practicing conservation just by doing research and publishing papers on shorebird population dynamics. Over time, I learned that there are many more steps between science and actually carrying out conservation action.

While in the field conducting my Ph.D. research in Brazil, I witnessed how people’s livelihoods in remote areas depended on healthy ecosystems. But our environmental policies often exclude people from accessing natural resources, creating a disconnect between people and conservation. Early in my career, I wanted to change that and help people understand shorebirds, their habitats, and why we should care for and work together to protect them.

How can we help people understand shorebirds and why they’re important?

We need to connect with people to help them understand why birds matter. Once you make those connections and share knowledge and experiences, it’s like a lightbulb goes off; learning about these birds’ stories can change people’s lives.

From there, it becomes a domino effect. As people become more curious and passionate about birds, they pressure government and federal agencies to fund research or protect natural spaces. Throughout my professional life I’ve wanted to put these gears in motion and connect people who could help scale impact and put science to work to improve conservation efforts.

What shorebird conservation challenges do you want to address in your new role?

I generally want to grow shorebird science and conservation in more parts of Central and South America. Many of the current research methods, policies, and conservation strategies that are applied across the Western Hemisphere, as well as the funds that help keep them going, come from the U.S. and other more developed countries. While it’s great to have those plans and practices in place at all, they don’t always work well in many Latin American countries.

Similar to how we have to translate ideas, science, and conservation needs into language that everyone can understand and use, we also have to figure out how to translate behavior, too. I sometimes feel like I’m some sort of hybrid having lived in both Brazil and the U.S. for so long, and I think that has given me the ability to adapt and better understand different cultures. There is a lot of work to be done and many differences in how countries operate, but I got a lot of practice recognizing those differences and using them to build partnerships during my work with SAVE Brasil to develop the shorebird program. That work also helped raise awareness about conservation issues throughout Brazil, so I think we’re already off to a good start.

Where would you like to see shorebird conservation in the Americas in 10 to 20 years?

We have some incredible people who work in shorebird conservation in the Americas. But compared to groups like the American Ornithologists Union or other, larger bird conservation collectives, the shorebird community in the Western Hemisphere is small and really just getting started. We’re currently learning the best ways to streamline what we know into more widespread conservation policies that cover all bird groups. In ten years, I want to see those policies include shorebirds in countries throughout the Americas. If we’re able to do that, I think it’s a reflection of our success in bringing awareness to shorebirds, a group of wildlife that is so often overlooked.

I would love to see people, especially children, see shorebirds and recognize what they are. I want to be able to go to a place and see people — who aren’t shorebird biologists — tell stories about those birds with love and enthusiasm. I want shorebirds to be the next sea turtles!

How do you hope people’s perspectives on shorebirds change as you continue to spread awareness in your role?

When I was first learning about birds living in Latin America, there was so much emphasis on the brightly-colored species that breed here or live here year-round. I remember when I decided I wanted to study shorebirds for my Ph.D., people asked me why I didn’t want to study “our” birds, or the birds that North Americans and Europeans come here from far-off places to see. I would respond, “they are our birds!” There are migratory shorebirds that spend more of their lives here [in the Southern Hemisphere] than the Northern Hemisphere — birds don’t have citizenships like people do, but they connect and belong to all of us.

Back to all

Back to all