Shorebird populations have declined by more than half in the last fifty years, due in part to loss of habitat. These long-distance migrants require safe feeding areas – commonly called “staging areas”– along the way to complete their migrations.

The Great Marsh, the largest contiguous salt marsh in New England, is one of these staging areas and has been identified by the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) and the National Audubon Society as an important bird habitat. The Great Marsh provides over 20,000 acres of crucial habitat for both breeding shorebirds and those migrating between their nesting grounds in the tundra and their overwintering areas in the Southern Hemisphere. During their stopover in the Great Marsh, they feed voraciously, doubling their weight so they have enough energy to complete the next leg of their migration. Tens of thousands of shorebirds will use the estuaries, tidal flats, salt marsh, and beaches in the Great Marsh to rest and feed.

This past August, conservation partners including The Trustees, MassAudubon, MassWildlife, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at Parker River NWR, Manomet, and volunteers conducted a coordinated shorebird survey over 1500 acres of the Great Marsh ecosystem.

Organizations have been surveying migratory shorebirds here, but this year marked the largest collaborative effort across the Great Marsh ecosystem to conduct simultaneous surveys with partner organizations. Work to conduct joint surveys began in 2021 and has only grown since then. This is the largest area of the Great Marsh that has been surveyed for migratory shorebirds at once. Additionally, the survey contributed to Manomet’s International Shorebird Survey statewide blitz. This effort brought people together to survey shorebirds between August 5-11. Eighty-nine observers counted 73,088 shorebirds, documenting 29 different species, across 115 sites in Massachusetts.

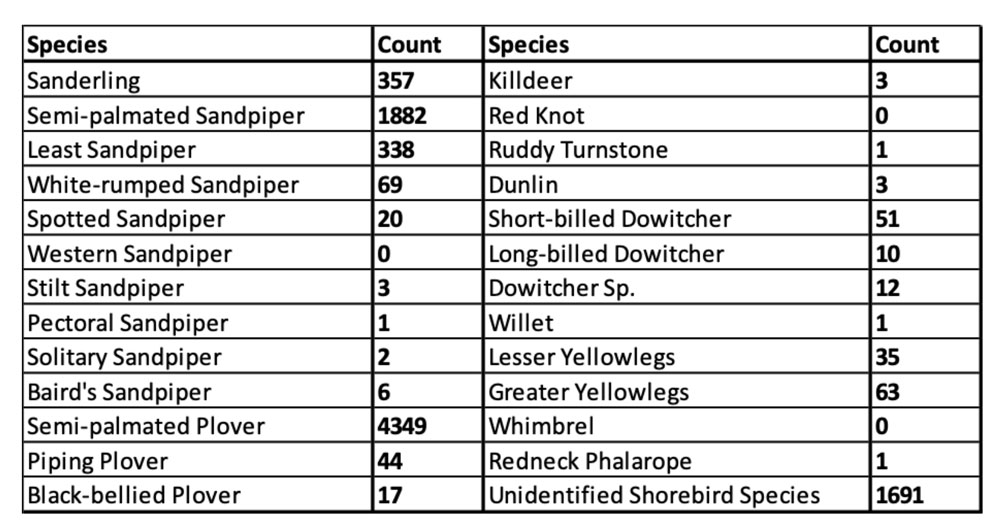

The survey was conducted at high tide when tidal flats (their primary feeding habitat) are flooded and the birds are resting or feeding on the beaches and high marsh not underwater. By surveying multiple sites simultaneously, we aimed to assess the population of shorebirds using the marsh at a single point in time during their migration. Sites included barrier beach systems like Plum Island and Crane Beach, as well as marsh areas in Salisbury, Rowley, Newbury, Ipswich, and Essex Bay. Sites were prioritized by where the highest number of birds are typically seen. During the survey, we counted a total of 8,959 shorebirds of 22 different species.

With at least 18,000 acres of marsh remaining to survey and since migrating shorebirds are in constant flux, this represents only a snapshot of total shorebird use, but it indicates the importance of the Great Marsh for these birds. In the future, we hope to expand upon this effort to better understand how the Great Marsh supports these declining species.

Back to all

Back to all