No bird species is synonymous with summer on the bluff at Manomet than the Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia). Their chattering calls herald the arrival of spring in late April, and their swift departure in mid-August marks the onset of fall migration.

It is impossible to walk through Manomet’s grounds during this window without hearing or seeing a Bank Swallow.

About Bank Swallows

Known as Sand Martins in the Old World, the nearly cosmopolitan Bank Swallow relies on insects for food, snagged straight from the air with acrobatic ease.

In North America, they breed as far north as Alaska, and once the summer bloom of insects has disappeared, they travel as far as South America to spend the non-breeding season.

Bank Swallows are birds that nest colonially in vertical cliffs or bluffs that can be easily excavated for their nesting burrows. While humans might view erosion as the bane of their coastal livelihoods, Bank Swallows rely upon it to create new nest sites.

Manomet’s bluffs provide just that, and Bank Swallows have been nesting by the dozens here since at least the 1970s and likely long before that. The first report of one at Manomet? July 20th, 1907, from the journal of George A.O. Ernst.

In the above photo, notice how the swallows have selected the layer of sediment best for a reliable burrow. Bank Swallows have been studied a great deal by the ornithological community.

Some of the interesting findings? Burrows average a depth of nearly 2 feet and are often in the upper 1/3rd of the bank, where they are less susceptible to ground predators. The nest is a shallow platform at the rear of the burrow made with plant matter.

If the burrow is re-used the following year, the nest is removed, and a new nest is constructed to avoid flea infestation.

Types of Swallows

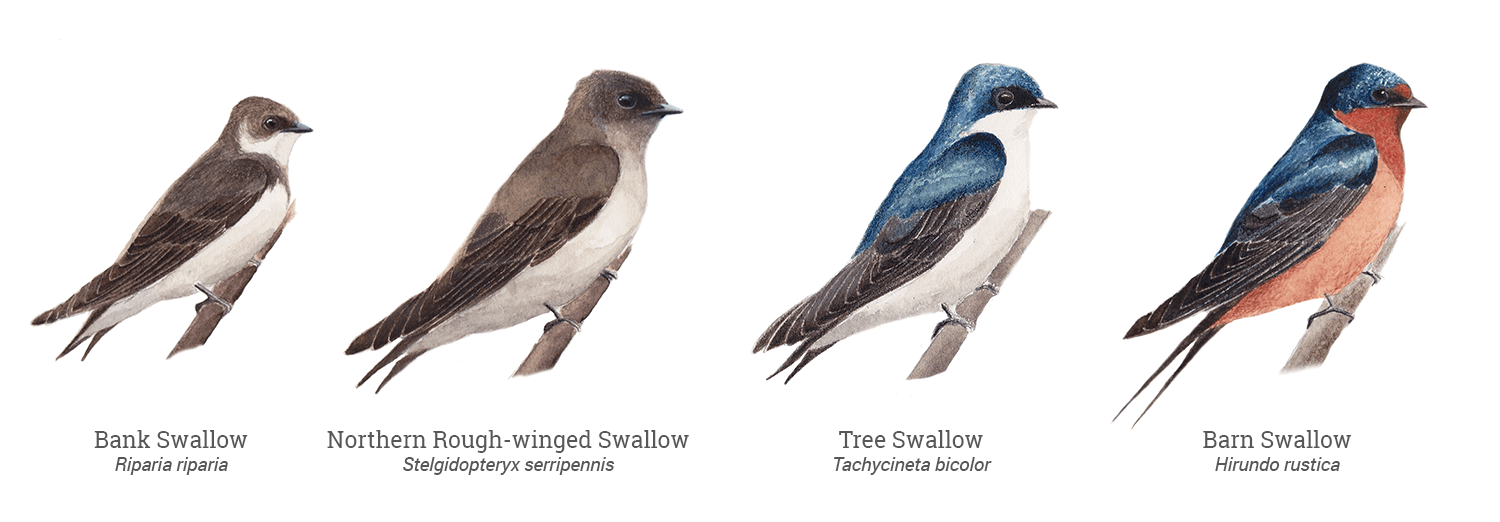

While Bank Swallows dominate the nesting scene along the bluff, three other swallow species are regularly seen at Manomet.

The Northern Rough-winged Swallow, which also nests in the bluffs in smaller numbers, is larger and duskier than the Bank Swallow and lacks a brown chest band.

Tree Swallows nest in boxes on the Holmes Farm and are abundant during migration, featuring an iridescent blue-green back and brilliant white underparts.

Finally, the Barn Swallow is a fairly common but rapidly declining species. It is easily identified by its ornate decorations, replete with a forked tail, iridescent back, reddish throat, and tan belly.

The Local Habitat

It might be easy to take them for granted here at Manomet, but away from their nesting colonies, Bank Swallows can be difficult to find. After the breeding season, they form mixed-species flocks with other species of swallows and can easily go undetected.

Furthermore, many species of aerial insectivores, including swallows, nightjars, and swifts are experiencing significant population declines. Why? Likely a combination of factors, including the rampant use of pesticides (which kill their prey) and loss of open space.

The habitat management methods we apply here at Manomet HQ aim to address these factors on a local scale, and as a result, the wetlands and grasslands of the Holmes Farm serve as an oasis for swallows all spring and summer.

The bustling activity of Manomet’s swallow colony

Some may wonder, do swallows ever get caught in our mist nets and banded? I asked Trevor to dig into the banding data; the short answer is yes. It doesn’t happen that often because swallows are loathe to dip below the canopy.

But, in our 50+ years of banding here, we’ve banded 106 Bank Swallows and 171 Northern Rough-wings.

Bank swallows are a reminder of the importance of protecting our ecosystem. We can all do our part to help these birds by supporting conservation efforts.

Back to all

Back to all