Shiloh Schulte, Ph.D.

SENIOR SHOREBIRD SCIENTIST

The drone of the Cessna 185’s motor had just faded into the distance when we heard the first Whimbrel calling as it flew overhead. It is difficult to convey the sense of relief and excitement from hearing that single call. Kirsti Carr and I had just been dropped as the first on the ground at a new field site on the Jago River in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, while the pilot went back to pick up the rest of the team, three biologists working for the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Kirsti works for Point Blue Conservation Science, but had worked with Manomet and the USFWS in previous summers conducting arctic shorebird research. Dr. Sadie Ulman, Robyn Thomas, and Zoey Chapman were the USFWS crew. This small, but highly capable team would spend eight days at the Jago River camp conducting rapid surveys for all arctic nesting birds and searching specifically for Whimbrel territories.

The Whimbrel research in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 2023 continued two prior years of tracking on the Refuge in close cooperation with Refuge Biologist Chris Latty and Dr. Rick Lanctot of the USFWS Migratory Birds Division. The specific goals of the Whimbrel project in the Refuge are to estimate breeding success, map post-breeding use of the Refuge and surrounding area, identify migration pathways, and establish connectivity with stopover and wintering sites on the Atlantic, Central, and Pacific Flyways. The refuge appears to be in a unique position where shorebirds from the refuge use all three flyways. In 2021 and 2022 we worked out of a camp on the Katakturuk River in the Western half of the coastal plain. In 2023 we wanted to extend the work further East in the Refuge to sample from a broader area and see if the percentage of birds migrating east and west would change with longitude. For over a year I worked on refining the habitat profile where we would expect to find the birds and on securing the resources needed to complete the project. Ultimately, we identified the Jago River valley as the best site to try to find more nesting Whimbrel. There was a short gravel bar on a large island in the river that would allow an experienced bush pilot to land, and the key habitat features of berry-laden river flats and adjacent wet carex tundra appeared to be present based on satellite photos. In addition, we recorded a pair of Whimbrel on a nearby PRISM survey plot in 2022. Still, we did not know how many pairs were in the area and how much ground we might have to cover to find them. With 12 tags to deploy and no helicopter at our disposal at this site we were limited to covering the vast area on foot.

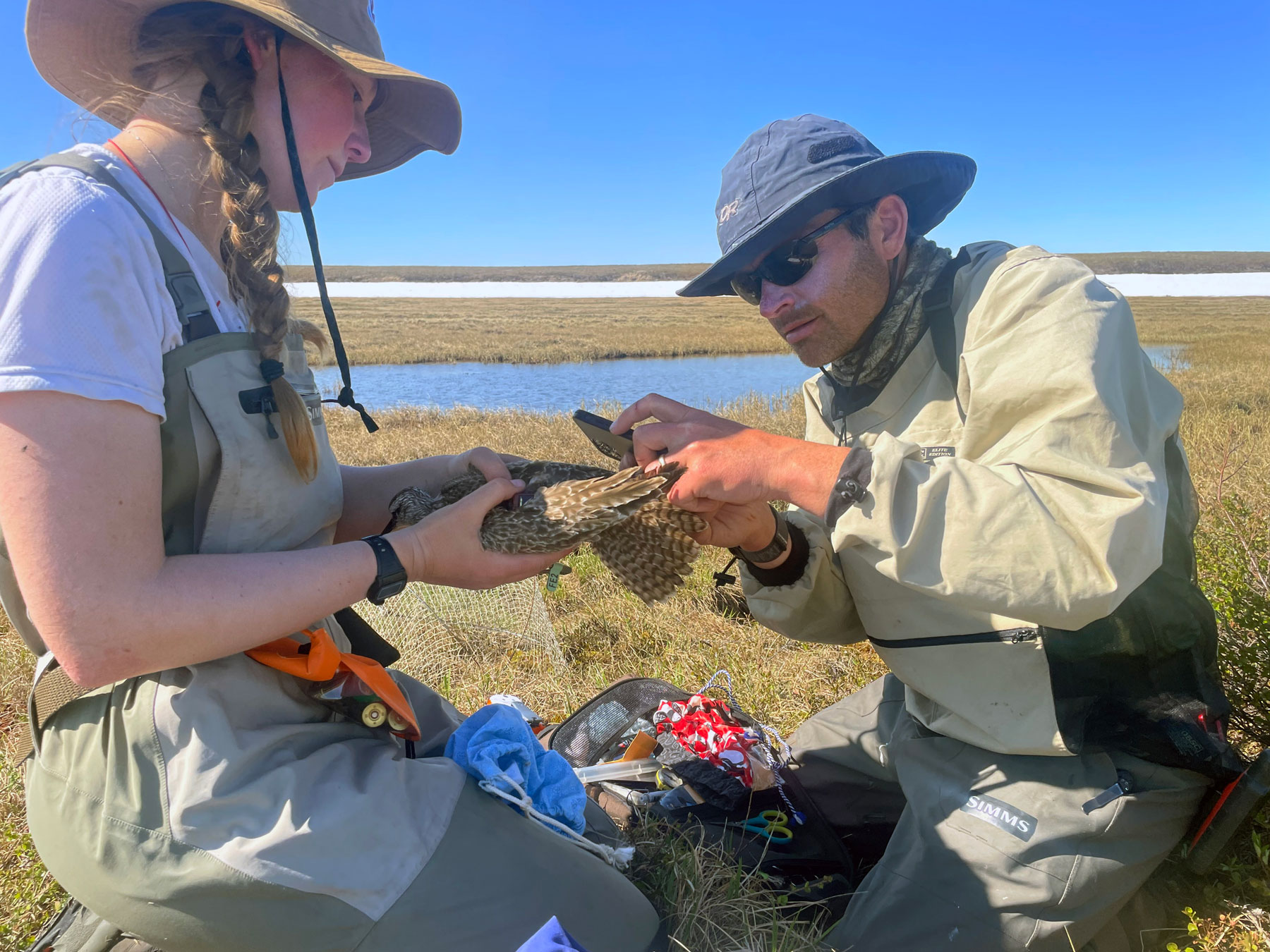

Hearing a Whimbrel fly overhead within moments of arrival, therefore, was a huge relief and a validation of the project site and plan. The team quickly set to work and we had a fully functioning remote camp set up within a few hours of arrival. On our initial scouting hike that evening we found two nesting pairs of Whimbrel and the first nest! The following day Kirsti and I successfully captured both adults from two pairs and outfitted all four birds with GPS satellite tags. These tags are solar powered and should continue to function for several years, which will allow us to remotely track nesting success in future seasons.

Unfortunately, despite the quick initial success and sightings of many more birds in the area, our search of the surrounding area found no additional nests. We realized all the other Whimbrel were flying across the river to feed on the flats and returning to nest sites on the far side. With the Jago River swollen by spring runoff from the mountains it did not look promising for the project. Luckily, we had a very experienced team and Robyn Thomas is a river guide as well as a field biologist. She was able to read the condition of the river and find a series of crossing points on the braided river flats that ultimately allowed us to safely cross to the far side where the birds were nesting. From that point on it was mostly a matter of endurance to finish the work. Kirsti and I would cross the river each morning and spend hours searching the expansive habitat on the East side to find and capture nesting pairs. Most days we walked about 12 miles in waders, and were in field for upwards of 14 hours. Despite the effort involved, it would be hard to imagine a more beautiful place to work. Just to the South of our campsite the foothills of the Brooks Range rise to meet the mountains, which form a stunning line of snowy peaks reaching to the horizon to the East and West. Jaegers, Whimbrel, Golden-plovers, Ptarmigan, and Lapland Longspurs are constant companions. A few hundred feet from our campsite a family of Red Foxes were denning and continued to go about their daily routine generally unperturbed by our presence.

Over several long days, we deployed 11 of the 12 tags. The last couple proved exceptionally difficult because of some equipment failures and wary adult Whimbrel. Few things are more frustrating than waiting hours on the frozen ground for the right bird to come to the nest only to have a trap fail to work at the critical moment. Still, through sheer persistence we managed to get all but one tag out with about 48 hours left on site. The morning before we had to leave I decided to try one more area we had not completely searched far downstream. About 5 miles from camp I heard alarm calls and found another small colony of nesting Whimbrels. Kirsti and Zoey made the hike down to the site and we set the trap on a newly discovered nest. Moments later we had a bird in hand and the 12th tag was on! A very satisfying conclusion to the fieldwork this summer and a testament to the perseverance and dedication of the crew.

The data from these 12 tags will contribute to the much larger effort by Manomet and key partners to build a complete ecological profile of the species in the Americas in order to develop management strategies to ensure long-term population stability. Large shorebirds like curlews and godwits are suffering global population declines and our goal is to use new tracking technology to learn as much as we can in order to stabilize populations and reverse declines. Manomet began its current work with Whimbrel in 2011 when we engaged with partners at the Center for Conservation Biology, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, The Nature Conservancy, and the Canadian Wildlife Service, in an ongoing study using satellite tagged birds from Georgia, Virginia, Mackenzie River Delta, and Cape Cod to study migration ecology and survival of adult birds. Currently, our Cape Cod effort to study juvenile Whimbrel migration is the only project focusing on movement and survival of this age class. The work is set to expand substantially with the addition of our Cape Cod Coalitions for Shorebird Conservation site led by Alan Kneidel, and with the expertise of our new Shorebird Biologist, Liana DiNunzio, based in eastern Massachusetts.

Concurrently with the Alaska and Cape Cod projects, we are tracking Whimbrel stopping over at sites in Texas and Louisiana. Manomet has a strong team working on this project, including Brad Winn, Shiloh Schulte, Alan Kneidel, Sam Wolfe, and Karis Ritenour. This work is cooperative with Paula Cimprich and Dr. Jeff Kelly at the University of Oklahoma. The primary goal of this project is to assess the use of agricultural lands by Whimbrel at stopover sites and to understand how Whimbrels are affected by wind and weather systems during long-distance migration flights. In addition, we are using the data from these tags to assess nesting success at breeding sites and to identify stopover sites, night roosts, and wintering locations. 2023 is our second year of tracking work in Texas with a total of 38 Whimbrels tagged at this location.

The GPS-tagged birds are already delivering interesting data this summer. As these birds leave their Arctic nesting sites their migration routes take them directly through the wildfire smoke blanketing much of central and eastern Canada. We will be watching closely to see how their flight paths or altitude might change as a result of the fires.

None of this work would be achievable without funding and close partnerships with organizations like the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Knobloch Family Foundation, the Mennen Foundation, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, as well as the direct support of many dedicated individuals who care deeply about these remarkable birds and the challenges they face.

Back to all

Back to all