Tim Sharpe

In the 1970s, Patty O’Brien arrived at Manomet as a young intern with a curiosity for birds and a passion for learning. That summer – spent banding birds, observing Gray Catbirds at dawn, and immersing herself in the rhythms of nature – sparked a lifelong love of science, conservation, and discovery. Though she later pursued a career in child psychology, her connection to birds has never faded.

In this conversation, Patty reflects on the experiences that shaped her—how a single moment on a childhood camping trip ignited her fascination with birds, how Manomet influenced her path, and how birding, conservation, and art remain central to her life today.

Q: You were an intern at the Manomet Bird Observatory Banding Lab in the 1970s. How did you learn about the opportunity, and what led you to Manomet?

A: Honestly, I don’t remember exactly how I found Manomet—it was a different time, without email or the internet! I was attending a nontraditional college in Vermont that required an off-campus experience each year, so somehow, I landed at Manomet for a summer. I wrote a lot of letters back then—on a typewriter!

Q: Were you interested in birds, wildlife, or the outdoors as a child? Was there someone or something that influenced you?

A: Several experiences drew me toward bird study and art, but one stands out. I was about seven or eight, walking with my dad on a camping trip in Michigan when a bird flew across our path. I asked him what it was, and he said he didn’t know—but that there were people who knew all the birds and plants. I remember him gesturing widely with his arm to the forest around us. This absolutely intrigued me. I thought, I want to know what those birds are!

Later, I found an old Golden Guide to Birds and was mesmerized by how beautiful they were. I spent an entire afternoon painting watercolors of them.

Q: What are some of your best memories from your time at Manomet?

A: So many! Living in the dorm, cooking with fellow interns, spending hours banding birds in the lab, and even shorebird banding at night. Holding birds in my hands—gently removing them from the nets, weighing, measuring, and inspecting them—was an unforgettable experience.

I was lucky to be mentored by Brian Harrington, Trevor Lloyd-Evans, and Bruce Sorrie, with Kathleen “Betty” Anderson leading Manomet. Her office had the most beautiful view over the cliff.

I took an ethology class at the Vermont college when I was a freshman, and we learned about Tinbergen’s study of how gull chicks react to the red dot on the parent’s bill – a “sign stimulus.” The chick’s pecking at the dot served as a stimulus for the parent to feed the chick through regurgitation. I found the behavioral part, and how it created an adaptive system that must spring from something inborn or genetic in the birds, of great interest. And at Manomet, I was particularly drawn to a behavioral study on Gray Catbirds. I’d spend hours at dawn huddled in the brush, observing their displays and taking meticulous notes. That project led me to present my findings at the Northeastern Bird-Banding Association conference—my first taste of collecting and sharing data, which shaped my future career.

At that same conference, I met Chuck Huntington, a renowned ornithology professor at Bowdoin. That meeting played a key role in my acceptance to Bowdoin, where I eventually transferred.

Q: What did you do after college and your internship?

A: At Bowdoin, I pivoted from ornithology to psychology, but birds were still a huge part of my life. I received a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to study woodpecker nesting behaviors in South America, delaying my graduate studies in Clinical Psychology. That year resulted in two publications and deepened my passion for field research.

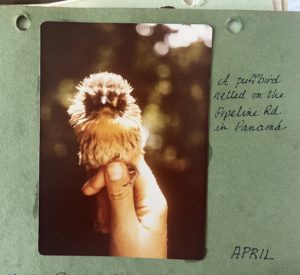

Even in graduate school at the University of Connecticut, birds weren’t far behind—I spent a summer as a research assistant for a bird-banding project on the Pipeline Road in Panama, thanks to my Manomet experience.

Q: Has your early experience in birding and conservation influenced your life over the years?

A: Absolutely. While raising a family and building my career limited travel, we still prioritized time outdoors—hiking, birding, and visiting national parks.

Now that our kids are grown, my husband Andy and I have increased our birding trips and conservation efforts. In addition to Manomet, we support organizations like American Bird Conservancy, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Bowdoin’s Kent Island Research Station, Audubon, and BirdLife International. We also contribute to local land trusts and field stations to help protect natural habitats.

Q: Your art prominently features birds. How do your artistic and conservation interests intersect?

A: I’ve been an artist all my life, mostly working in pen and ink, watercolor, and more recently, collage. Birds inspire me in two ways: their sheer beauty and their fascinating life cycles and migrations.

Q: You’ve had a career in child psychology—do you see connections between that work and your interest in nature?

A: They aren’t necessarily connected, but they’re parallel in a very important way. They both involve complex systems in which the components interact dynamically. Birds live in specific environments, as do humans. Birds either thrive or are stressed due to the interaction between themselves as organisms and what in the environment supports or thwarts them, and this applies to humans, as well. In both arenas, I appreciate the beauty when the whole system creates a thriving community and individual, and I am spurred into action when things falter.

Back to all

Back to all