Citizen Scientist Meet Citizen Plover.

It’s a misty dawn on a mythical coastline somewhere on planet Earth. A woman with binoculars and a walking stick passes through a thick veil of morning fog and treks through a series of marshes and trails. When she arrives on a pristine stretch of beach, she stops at the sight of a flock of rare plovers feeding. Feverishly making notes in a small leather journal, she counts the birds, studies their surroundings, and tracks their behaviors. As she marvels at the encounter, one of the half-dozen birds stops feeding just long enough to make contact with this interloper — a long, intense gaze as if he has something important to say.

Scenes like this play out countless times a day all across the world. These local volunteers and birders — citizen scientists — along with ecologists, biologists, scientists, statisticians, corporate partners, and government employees, are an integral part of an impressive and collaborative network – the ‘secret sauce’ that defines Manomet and extends its scope and impact far beyond its size.

It Started With a Question.

When Brian Harrington dreamed up the International Shorebird Survey (ISS) in 1974, the questions were simpler – and the stakes far less dramatic. Born out of the Christmas Day Bird Count, his idea was to enlist, empower, and engage locals to chart shorebird populations and shed light on the journey from the Arctic to the shores of the Americas. It grew from Manomet’s roots as a volunteer- led organization and a couple of hundred boots-on-the-sand individuals to over 5,000 volunteers today across the Western Hemisphere. Back then, no one could have predicted the impact these data would have – or how a recent analysis would cause a seismic shift in shorebird conservation.

Data Points: Steep Shorebird Declines.

“The shorebird population is tanking,” says Manomet’s VP of Science, Stephen Brown, Ph.D., and shorebird science veteran who supervised the analysis of 40 years of data from the ISS and helped pen the paper published in the Spring of 2023. “Of 28 shorebirds assessed, 19 were showing significant declines that placed them on the global threatened red list.” Brad Winn, VP of Resilient Habitats at Manomet, calls it a ‘holy crap’ moment (admittedly not exactly a scientific term). “We assumed there was a decline with some species, but we learned more were involved than we had been thinking, and the decline was much greater than anyone imagined, spanning over three generations.”

At the epicenter of this bird- ageddon moment was Manomet’s new President, Elizabeth (Lizzie) Schueler. She recalls that one of her first herculean tasks was to spur the translation of a stockpile of data into a meaningful conversation. When no one could tell her what was in the data, she queried, “If we don’t know, then who does?” This question sent Stephen Brown and his team into action, partnering with Canadian Paul Smith and his team in a year- long dedicated analysis using sophisticated statistical models. If the numbers were speaking for the birds, they had a very clear message: they are in real trouble.

From Passion Projects to a Passionate Purpose.

“It was time for Manomet to change our lens in terms of what we were doing and how we were working. Someone had to make some hard decisions to better focus the organization. Lizzie explains that her focus leading Manomet has been exactly that – to focus. Smaller scattered passion projects gave way to a unified and clear purpose and a lofty mission: to improve the health of flyways and coastal ecosystems, and more specifically for our shorebird work, to reverse the decline of shorebirds. Since Manomet wrote its current Strategic Plan, 190 countries under a United Nations convention have committed to restoring or protecting 30% of our biodiversity, which includes halting and reversing extinction of species. It turns out that targeted monitoring and measuring is imperative for this work to be successful. Just ask the Oystercatcher.

A Resurrection Story.

It is now an almost infamous case study of the recovery of a bird population. The initial goals were to increase the numbers by 30% in ten years. Dr. Shiloh Schulte, Ph.D., who coordinated the American Oystercatcher Recovery Program, explains that the secret was to have baseline population data and then to ask focused questions and pinpoint the limiting factor. “We went deep into the data and found the problem was with ‘hatching and fledging.’ With the right entry point to the research, we were able to apply it to the field – remove the disturbing factors – and see real change.” Combining aerial monitoring and on-the-ground confirmation tracking, the work has yielded an increase in the populations of Oystercatchers of 42% over 15 years.

It has become a framework and a model to replicate. Next up, Manomet will be using a similar monitoring and measuring approach to help restore the Whimbrel population, and just received a three-year $1.2 million grant to do so. “We have proven that when we are focused and use data and state-of-the-art monitoring and measuring – the results follow,” says Schulte.

The Proof Is in the Plover.

Meanwhile in South America, Arne Lesterhuis, Shorebird Monitoring and Conservation Specialist at Manomet, is working with local partners and other team members with a focus on resident birds, so-called South American endemics. The Coastal Shorebird Survey encompasses five countries including Peru and around the tip to southern Brazil. He is enthusiastic about the challenge, “It’s a bold strategy to get population estimates and monitor all South American birds.” Already, they have been surprised by what they found out with the Magellanic Plover. Initial estimates set in the early 2000s were between 1,500-7,000 individuals but the data Manomet and partners collected revealed that there appeared to be fewer than 500 left. In November, they will begin to track another resident species, the Diademed Sandpiper-Plover. Arne says, “Manomet has prioritized resources to gather data that will enable us to make the case showing the urgency of this work. In so doing, we have been able to work with and train local partners on satellite tagging techniques which bolsters local capacity to keep this work going.”

From Sky to Warming Sea.

Though the global shorebird work is central to Manomet, understanding marine life and their ecosystems remains a priority as well, and nowhere is measuring and monitoring more important in the face of the rapidly changing climate than the Gulf of Maine. Marissa McMahan, Ph.D., Senior Director of Fisheries, from a 5th-generation Maine family, is perfectly suited to helm that ship. She explains how Manomet is uniquely positioned to be a leading voice in this conversation. “The waters in our part of the world – Maine – are warming faster than 99% of the rest of the world.” The stakes here are deeply personal because the work is intrinsically tied to human livelihood. The data not only give the big picture of what’s happening to marine life and ecosystems but is used to communicate with fishermen and those writing fisheries policies to create a conversation around the changes. For example, when the blue crab started to appear in the Gulf, the local fisherman thought it was a fluke and that some human had just dropped them in. Manomet’s hand-built crowd sourcing website for blue crabs enables anyone to upload where they have seen crabs, which now shows them popping up everywhere.

When Marissa’s team created this mapping site, it put the blue crab on the map – literally. For the fishermen, often working in isolation, it connected the dots and gave them visibility into the bigger picture. “We give them a seat at the table. It’s this kind of open-access science that Manomet’s reputation for building relationships is built on. And with the advent of new tools and technologies like acoustic tracking or DNA sampling in the water, we can collectively make better decisions about how to preserve the ecosystems and protect their livelihoods. We are really deeply committed to understanding how we can find pathways forward where people and nature can thrive together, protecting both the species and the commerce that puts food on the table.”

Technology Footprint: Going Forward.

Despite all the moving pieces to reach Manomet’s ambitious goals, Lizzie is passionate about what technology can help us do to accelerate monitoring. “We don’t know what the next paradigm is, and we can’t even fathom, for example, what Artificial Intelligence can do for us. We are currently using AI for the first time to help us make sense of the equivalent of 40 years of acoustic data we gathered this past summer in the Arctic over a 3.65 million acres range. Technology has grown our knowledge exponentially. We are a small organization in a very large world addressing big challenges. Technology and partnerships are imperative if we are to reach the scale of impact we aspire to, and technology helps us monitor more species faster and more efficiently.”

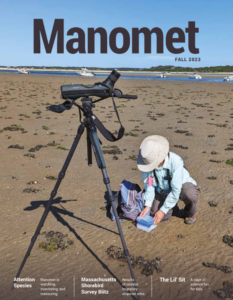

Lizzie underscores Manomet’s dedication to results, and the importance of measuring in order to manage species and resources. She says, “We are one of a few remaining organizations that has a staff of scientists who are in the mud and sand on a regular basis working to understand how our world is changing, and developing strategies to address these changes.”

Shiloh paints a picture of what that impact looks like in the real world, “We want the skies filled with shorebirds. I want my kids to see the flock of western sandpipers overhead and not have just a story about something that used to happen in a previous century.”

Manomet Magazine

Fall 2023

Attention Species: Manomet is Watching

The Lil’ Sit: Science for Kids

Happy Trails: Kathleen (Betty) Anderson Dedication

Massachusetts Shorebird Survey Blitz

Back to all

Back to all