Trevor L. Lloyd-Evans

Senior Fellow

To celebrate the 50th consecutive year (1974 – 2023) of the Plymouth Christmas Bird Count (CBC), we bundled up on December 27th and covered the woods, fields, shorelines, beaches, rivers, ponds, suburbs, and town within the standard 15-mile-wide circle based on Plymouth. We also restored the in-person evening count at Manomet Headquarters (Manomet Bird Observatory) for those who chose to attend.

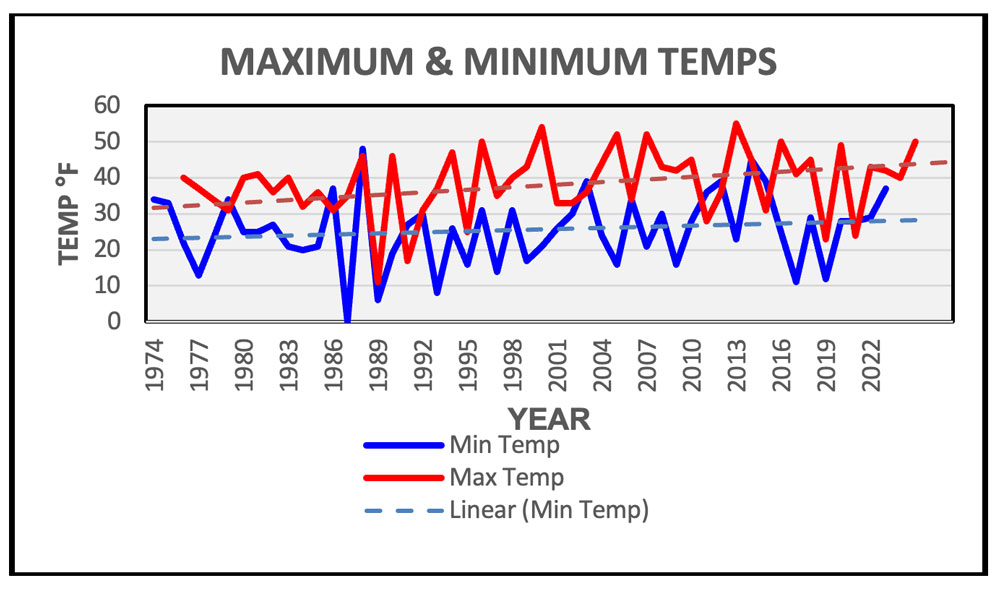

Temperatures ranged from 37°– 50° F with no precipitation, a complete cloud cover all day, essentially no wind, and there had been no snow to date. Owling coverage was good and we could hear every chip and chirp all day; all water was open.

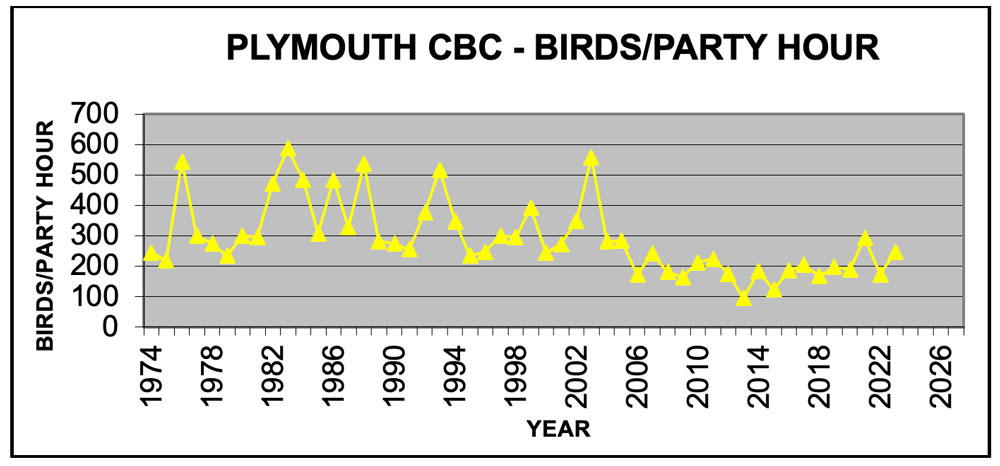

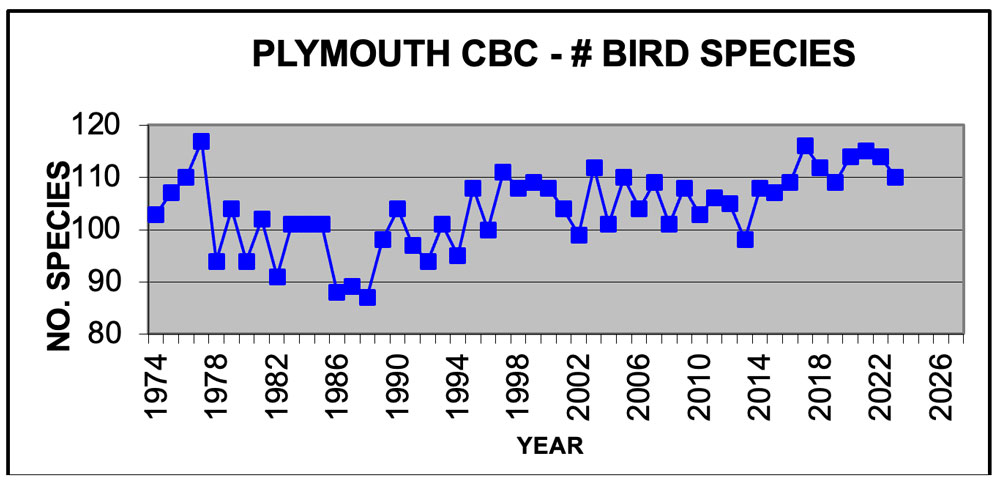

The final total of 110 species in 72 party hours was 6 species above the long-term average. There were no irruptive northern species, but because both high and low daily average temperatures have increased by about 5°F since the early 1970’s, this may have partially accounted for more migrant birds lingering in our area.

Ten all-time high counts this year were: Black Scoter (1,142), an amazing more than 800 above our previous high count of 325 in 1993; Long-tailed Duck (466); Purple Sandpiper (ca. 257) nearly 200 more than our previous high of 61 in 2000; Great Horned Owl (11); Golden-crowned Kinglet (117); Ruby-crowned Kinglet (12); Swamp Sparrow (69); Palm Warbler (9); Pine Warbler (27) and Western Tanager (2). We had previously recorded single Western Tanagers in 1983, 1993 and 2019. A snowy Egret in Plymouth Harbor was our 2nd (the 1st was in 2005). Encouragingly, no species was tagged as record low this year.

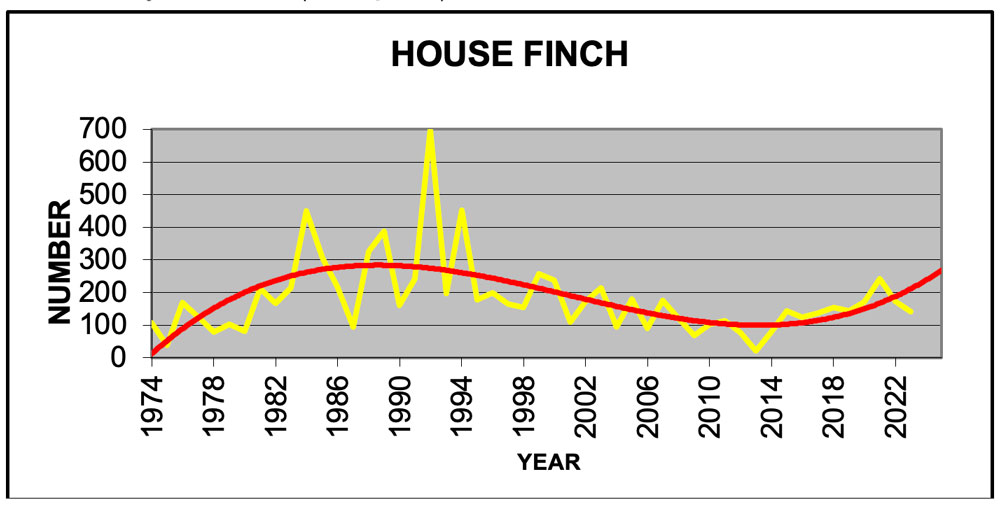

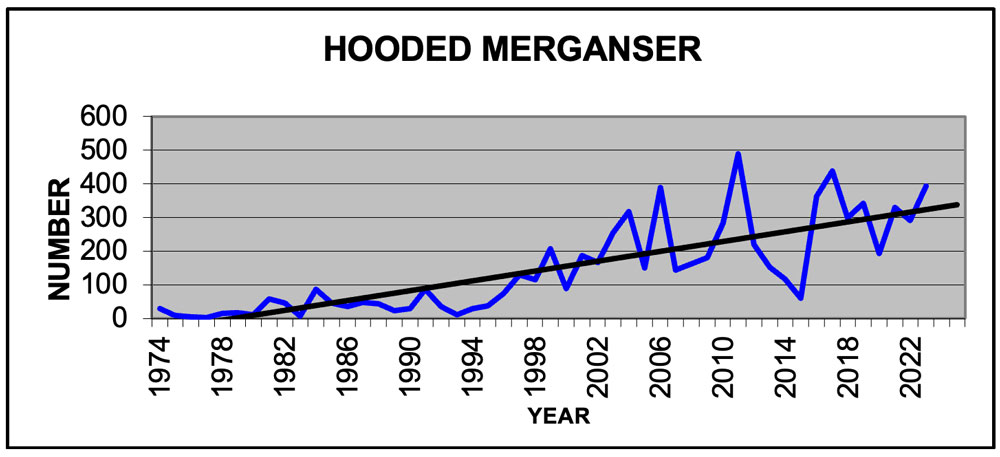

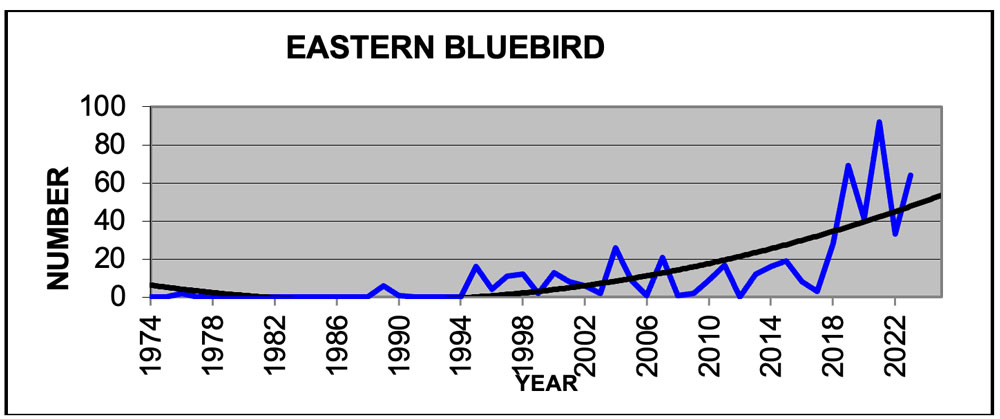

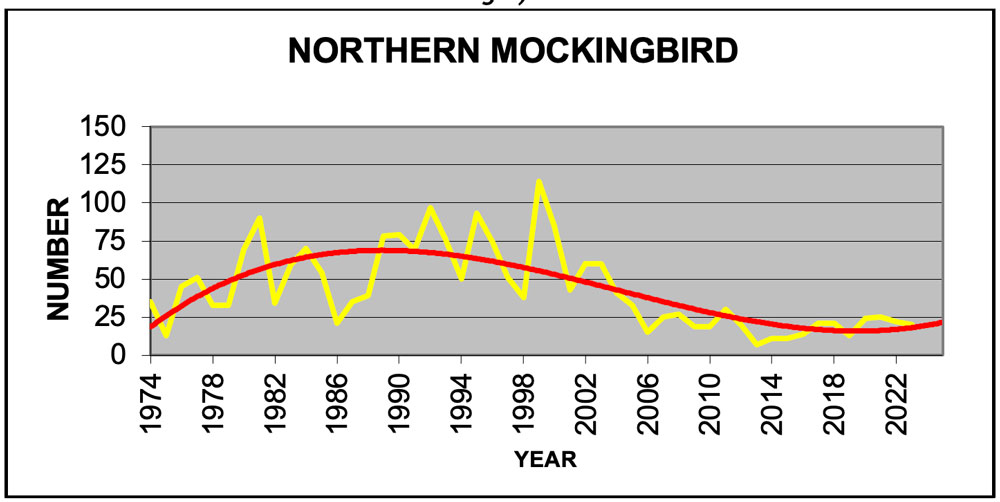

A warm, wet, and not snowy December, plus the aforementioned climate warming trend, may have resulted in several positive features of this count: a) More formerly obligate migrant species may have lingered, or may even now overwinter, thus claiming prime breeding territories in spring, e.g. the Turkey Vulture, Hermit Thrush, Am. Robin, Pine Warbler, catbird: b) Permanent resident species e.g. mockingbird, Carolina Wren, and House Finch may be surviving winters in increasing numbers: c) “New” permanent residents e.g. Red-bellied Woodpecker, N. Raven, and turkey are showing rapid increases in numbers: d) A warmer early winter may encourage shorebirds and waterfowl to stay north longer as saltwater bays, mud, and fresh water have not yet frozen solid.

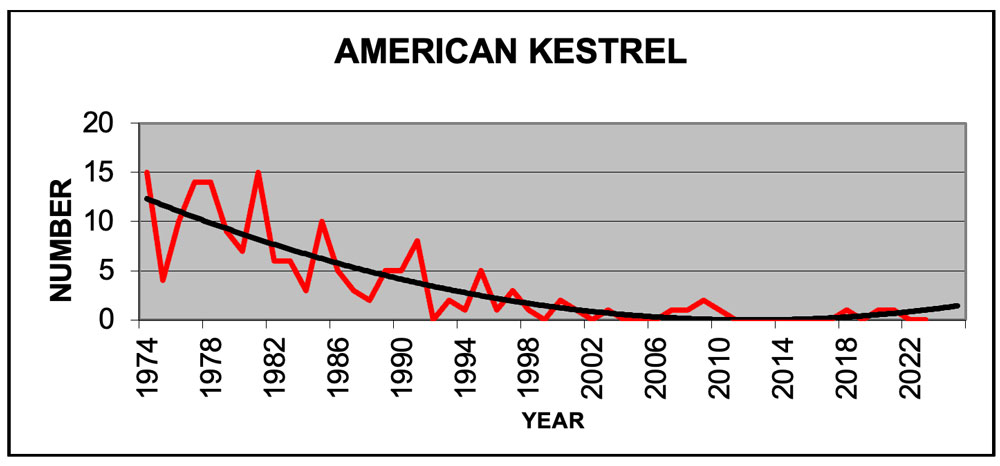

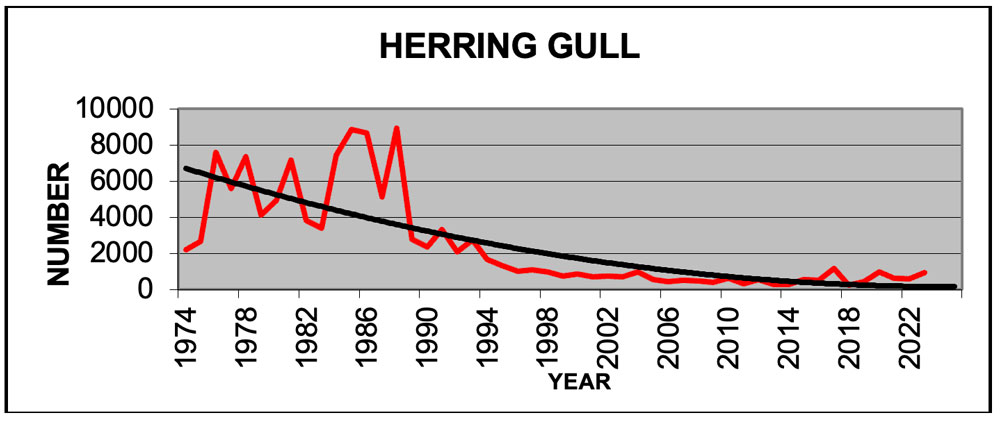

Perhaps a negative trend has been for northern-breeding irruptive species to be able to stay north of Plymouth, especially if they have adequate food supplies. Where are the hundreds of Evening Grosbeaks we counted every year from 1974 – 1983? Or the Pine Grosbeaks or Boreal Chickadees? Of course, many species are declining for a variety of other reasons, including reduced habitat in North, Central and South America, broad climate change effects, declining invertebrate prey, persistent chemicals, pesticides, herbicides, and other anthropomorphic factors. Open dumps are closing (there is evidence of long-term declines in large gulls and starlings), sea levels are rising, storms are becoming stronger as the tropical Atlantic and the Caribbean are heating up, and the Arctic is melting. These are just a few of the causes of the 30% average drop in numbers of N. American birds since 1970 (which translates to almost 3 billion birds gone), a figure supported by Manomet’s International Shorebird Survey and our land bird migration monitoring at the Manomet Banding Lab since 1966.

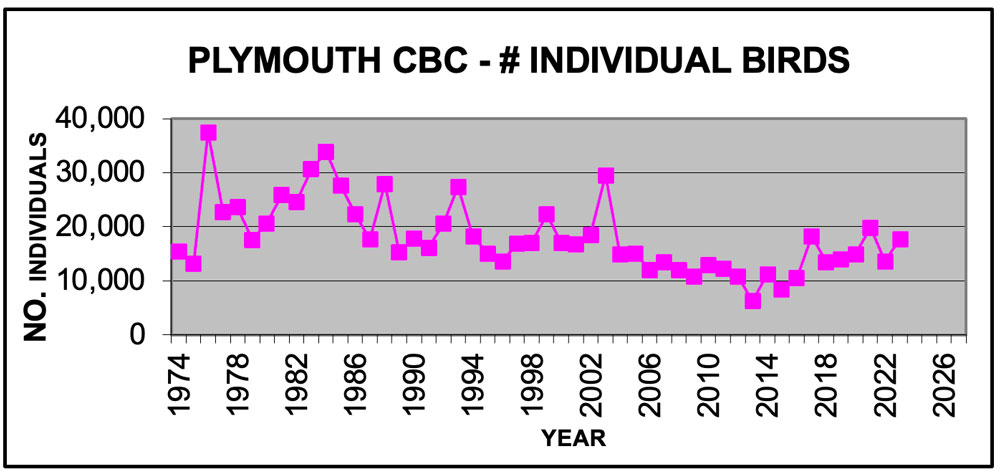

On a more cheerful note, this year our regular counters in the field were again up early, long, and late, supplemented by birders from The Pinehills in Plymouth. Many thanks to all the stalwart birders in the mild but foggy outdoors, plus the feeder watchers (27 total participants), who all contributed to a count of 17,749 birds of 110 species.

After a redemptive year of birding in 2024, may your favorite coffee, tea, and hot chocolate shops be open again (early), and may the evening-tally stewpots and garlic bread be provided as of yore. I hope we actually see you all in person again next Christmas.

Back to all

Back to all