Stephen Brown, Ph.D.

VICE PRESIDENT, SCIENCE

Stepping onto the tundra for the first time this season felt like coming home, and also like the culmination of my career. The morning sounds of the tundra filled the air. Birds everywhere were singing to advertise their territories over the steady howl of the always-present tundra winds. They darted against the huge tundra sky that reached from horizon to flat horizon. I was visiting a plot I had surveyed 16 years ago, although the thousands of plots I have surveyed since then meant that I had no particular memory of this one. But the arctic sights and sounds were all so familiar: the sharp slap of strong cold wind in my face; the cold, wet, soft ground of the marsh underneath my feet; and the swirling bird flights all around me with a symphony of sounds you can only hear on the tundra during nesting season.

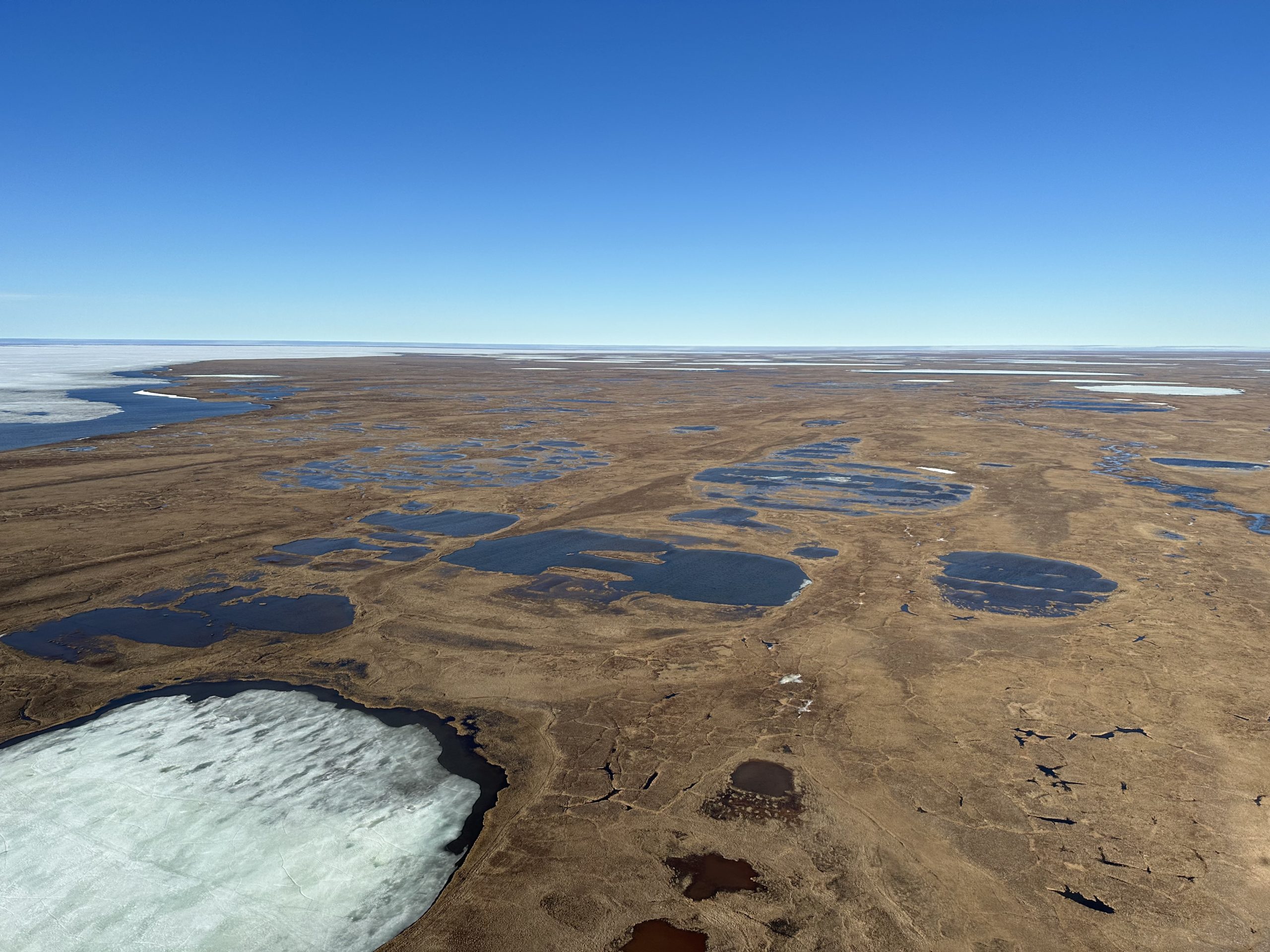

We returned this season to the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area in the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska—a mouthful of a name for sure, but one of the largest areas of public land in the country. The title of the paper our team wrote based on our earlier surveys says it all: “Shorebirds Nest in Unusually High Density…” in this special place… If one were to pick out a part of the north slope to set aside as a wildlife refuge to benefit shorebirds, the Teshekpuk Lake area would have a strong case as a prime contender. The numerous wetlands, small ponds, and large lakes make this region extremely attractive to both shorebirds and waterfowl. And this is only the second place we have returned to so far to measure how shorebird populations have changed over time.

Our results from ongoing migration surveys, just published this spring, are not encouraging; they show ongoing declines for many of the species that migrate along the Atlantic Flyway. These counts serve as an early warning system. But migration counts are always highly variable, you could go to the same area on one day and see many shorebirds, and then see very few the next. So, we designed these arctic surveys to get a highly precise measure of shorebird populations over time. The best shorebird scientists in the hemisphere worked together for almost a decade to develop and perfect the system, which relies on rapid surveys at many randomly chosen sites, with a correction rate for birds missed in the rapid surveys determined through intensive surveys on a small sample of sites where we compare full season counts with the same rapid surveys we do across the landscape. Here on the tundra, the birds are using territories they defend with song and display – just like common birds everywhere do—so we can measure their populations more precisely. In many ways, last season in the Arctic Refuge and this season here represent a culmination of a career-long effort for me and the partners working to implement the program.

This year we are continuing our parallel study to see if small audio recording devices can help us measure what birds are present and how many of them there are. Shiloh and James did a remarkable job deploying over 120 of the units across the entire special area, and they are busily recording bird song all summer. We will mount a separate expedition in August to retrieve them, before our partner Nicolas Lecomte at University of Moncton begins the long process of reviewing all 4.5 years of sound recordings through a machine learning program.

We always need a strong team to do this work in the harsh conditions of the arctic. Our team this year draws from both Manomet staff and biologists from partner organizations as well. Shiloh Schulte, Metta McGarvey, and I represent Manomet, while Kirsti Carr is working with us on loan from Point Blue Conservation Science, River Gates from Audubon, and Rick Lanctot is our long-term collaborator from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Our pilot, James Dobson, flies for Pollux Aviation, a group that has seen us safely through many seasons. His exemplary skill managing everything from fuel needs to weather challenges to avoiding disturbance to other wildlife is a huge part of our success. Together, everyone functions as a well-oiled machine.

So many things had to come together to make this work. Our major funders, including the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Land Management, provided the key support to make the work possible. Matching contributions came from many private donors who see the value of conservation science to guide recovery efforts. The support staff at our headquarters are always working hard to make sure we can carry out our work. Metta performed her usual magic with logistics, making everything we need appear where and when we need it—no small challenge in the arctic—as well as keeping all of us and the project on track through many months of meetings and planning. Sarah Saalfeld, also of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, supported the project in many ways, including laying out the plots to be surveyed.

These surveys will provide the best data available on arctic shorebird trends—but there is much work left to do. We work with partners at Manomet and organizations across the hemisphere to conserve shorebirds and their habitats from here in the arctic all the way to their wintering grounds in Central and South America.

At camp after another long day and settling down in my tent, trying to sleep in between the loud slapping of the tent in the strong arctic wind, it’s comforting to know that our colleagues and partners are also hard at work across the huge range of these special birds. All the birds really need is for us to give them a chance, to understand what they need, preserve their critical habitats, and let them live their remarkable lives. Thank you for your help making sure that they can.

Back to all

Back to all