With heavy hearts, we share the passing of Manomet’s Founding Director, Kathleen (Betty) Anderson. Betty passed away on Friday, August 24, 2018 at St. Elizabeth’s in Boston at the age of 95. She founded Manomet Bird Observatory in August 1969, and served as our Director through 1983.

To all who knew her, Betty was a visionary. Betty was deeply committed to long-term research because she felt it was essential for understanding long-term environmental change. And she knew that from understanding can come action.

Born June 15, 1923, in Livingston, Montana, Anderson grew up in southeastern Massachusetts with a strong interest in nature thanks to her parents. A self-taught ornithologist, Anderson worked for the U.S. Public Health Service in Southeastern Massachusetts just following a serious outbreak of equine encephalitis in the 1950s. As part of the agency’s study of whether wild birds were transporting the virus, Anderson directed the netting and blood sampling of birds on Duxbury Beach.

By the end of 1966, Anderson’s research proved that the virus was not being carried from the north by birds. It was against this backdrop—having assembled 40 volunteers—that Anderson and Rosalie and John Fiske began to consider locations for a permanent bird research station on the South Shore. Betty knew through her local contacts about the property that would become Manomet, and arranged with the owners to set up an ongoing banding station there. Mist nets were operated at both Raynham’s Hockomock Swamp and Manomet for three years, before Manomet opened as a permanent research station in August 1969.

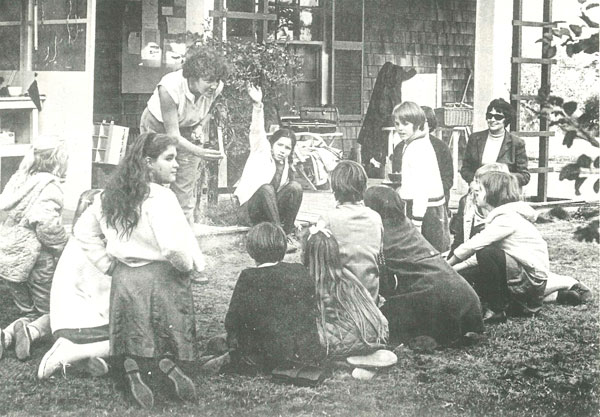

“I envisioned Manomet as being a low-key, full-time research station, a place where students and volunteers could, with a minimum number of professionals, work together, increase knowledge about bird biology and give young people…the stimulation of being exposed to birds and people working with birds,” Anderson said in the 30th anniversary issue of Conservation Sciences, an earlier version of the Manomet magazine.

“Now entering our 50th year, we should be proud that the mist nets at Manomet continue to tell us stories about how the natural world is changing, and why. Tens of thousands of children and adults have become connected to nature through the banding program Betty started. Interns under Betty’s guidance in the 1970s have gone on to be doctors and professors and conservation leaders and even business leaders across the country, all with a sacred connection to nature because of Betty,” said John Hagan, former Manomet President.

At the 100th anniversary meeting of the American Ornithologists Union, Anderson calculated that a quarter of the participants had a prior association with Manomet. “Manomet was everywhere. Students were giving papers, becoming known for their research. I’d say that was one of the great rewards,” Anderson said in that same interview.

Among her many awards, in 1995, Anderson received the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology’s Arthur A. Allen Award for her outstanding contributions to ornithology. She was the first person without a Ph.D. to earn this prestigious prize. She also published more than 60 papers in the fields of distribution, migration, conservation, populations, banding, and more in ornithological journals and lay publications.

“In a time when everyone seems focused on how to solve problems at “scale” across large geographic space, I wonder why we don’t place more emphasis on scaling our impact through time, not across space,” added Hagan. “There are no metrics to measure Betty’s impact over time. I suspect her positive impacts on the world will continue to flow abundantly for at least another 50 years through Manomet.”

Some remembrances of Betty from those who knew her best…

Trevor Lloyd-Evans, Manomet science fellow and first full-time employee hired in 1972

Tributes to Betty (Kathleen S. Anderson) are already springing up and accumulating at Manomet from an astonishingly wide range of those who were lucky enough to know her. In other writing, we at Manomet are praising her as a founding inspiration, an executive who led by example in all matters, and a self-taught scientist with an astonishingly wide range of interests. She was an enthusiastic field biologist and a born educator for audiences of all ages. The people inspired and the conservation research engendered would never have happened without the solid foundation of Betty’s early vision and energy.

But all of us who knew her well, rapidly turn the conversation to some version of “on a very personal level ….” From the earliest transatlantic correspondence when Betty hired me away from the British Trust for Ornithology, to long days working together in the mist-net lanes of Manomet and the Banding Lab, it was clear that Betty was your friend. On long road trips for conferences (and always for birding along the way) she was fascinated to learn about your experiences, your family history, and your opinions about every aspect of life in general. In return, you would hear of her long family connections from Massachusetts cranberry farming, to Montana ranching, to distant immigration from the old world. I cannot think of another friend who has the same enthusiasm about everything!

Above all then, Betty was someone who loved to share the results of her insatiable curiosity and turn this to practical use in the world around her. We owe much to her, but this is not really a time to express excessive regret for her loss to all of us. My feeling is that she was about ready to go onwards and see what happens next.

Brian Harrington, Manomet’s Senior Scientist Emeritus and also one of Manomet’s first staff members

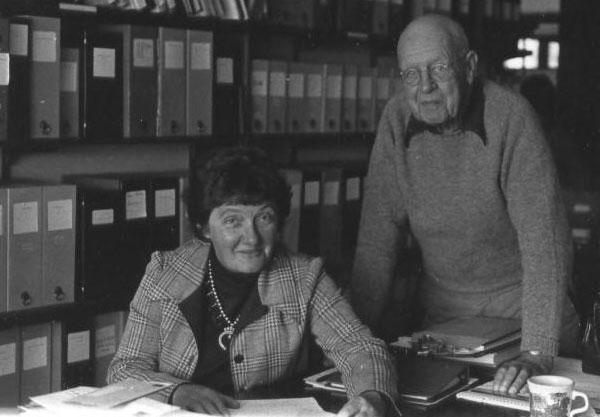

Kathleen S. Anderson’s name is tied to hundreds of Manomet’s earliest banding records, to administrative documents during the first decades of Manomet Bird Observatory’s existence, and to the future and careers of staff like myself and the many students who grew under Betty’s tutelage. I often reflect on what made Manomet flourish in its early history, and always return to the pivotal role that “KSA” played. Quite simply she was the biggest powerhouse of enthusiasm I have ever known; that enthusiasm was contagious, and it underpinned the early years of Manomet’s fragile growth.

A second pivotal element was Betty’s trust in people, and especially her staff. “No” was a rare word in her office—“Let’s try” was her modus operandi. That kind of leadership led to Manomet’s steady growth and to its becoming an internationally respected research and conservation organization, so setting the stage for what Manomet, Inc. is today. Betty loved people, she loved nature, and she had an unstoppable curiosity. In my mind, this glowing, self-educated woman was pivotal in building Manomet for our world.

On a more personal level, Betty was among the warmest people I have ever known. When I arrived at Manomet in 1972 (one of the first employees), she and her husband, Paul, regularly invited me for meals in their home, for weekend canoe trips, and for birding trips. In work, Betty was often one of the first hands to jump aboard our tank-like truck with me and six or eight interns for all-night shorebird banding trips on Plymouth Beach, and then return at dawn to face a day of work in the office. She could amaze all of us with her ability to swiftly remove a hopelessly tangled sandpiper from our mist nets, while cheerfully chatting about the shooting stars, the glow of the dawn, or some recent botanical find she had made. Many times I have heard former students say that their internship with Betty and the staff at Manomet was one of the most formative periods in their lives. I personally know the truth of this. Her mark is indelible. She will be missed by hundreds—perhaps thousands—of friends and professional associates throughout North and South America.

An interview with Betty Anderson

In 2010, we interviewed Betty about cranberry farming at our Harvestfest. Her great uncle was one of the very first cranberry farmers in Massachusetts.